First steps to running a web service on a Raspberry Pi - wimvanderbauwhede/limited-systems GitHub Wiki

First steps to running a web service on a Raspberry Pi

The purpose of this guide is to give you an overview of what you need to know if you want to use a Rapberry Pi as a server, for example to run Pleroma or Mastodon, or a simple web site or any other service.

After reading this guide you will be able to follow any tutorial for setting up a specific service on your Raspberry Pi.

The guide explains the following basics:

- Networking

- Services, servers and clients

- Use of the command line and remote access

- Files and folders

- Users and permissions

- Installing software

- Building software

- Setting up and running services

Note to experts:

- This guide only covers the very basics

- I have simplified many concepts for the sake of clarity and brevity

Networking

Since you want to run an internet service, let's look at the very basics of networking.

Connectivity

The Raspberry Pi 3 can provide network access via either a wireless (WiFi) or a wired (Ethernet) interface. An interface is part of the computer hardware that connects the computer to the network. Both of these interfaces to the network have a unique identifier called MAC address, and they also have a name like eth0 and wlan0. You may sometimes need the name or identifier for certain network administration tasks. We'll see later where you can find them.

IP address, host name, domain name, DNS

This section explains the basic concepts behind networking on the internet. It only deals with IP version 4 (IPv4), not with IP version 6, because that is still the most widely used and it is easier to explain.

IP address

The internet uses addresses consisting of four groups of numbers, each number between 0 and 255. Each network interface on a computer is assigned such a number, called IP address. The addresses are usually written with a dot between the numbers. For example, the Wifi interface on your laptop might have the IP address 192.168.71.88. The Ethernet interface will have a separate IP address, so your computer can have more than one IP address.

There are four types of IP addresses:

- public: only these addresses are accessible via the internet. For example, the search engine Qwant has the IP address

194.187.168.100. - private: meaning they can't be reached from the internet, like the IP address of your computer when it is connected to a WiFi network or an office network. They start with

192.168,172.16to172.31or10. - automatically assigned or self-assigned: these start with

169.254and are used typically when you connect two devices with a network cable. - local to your computer: these start with

127.0. The most common one is127.0.0.1. This range of addresses is special: while the public IP address can be considered like a street address of a house, and the private ones like a flat number, the local address is more like calling your house "home". Local addresses are not assigned to any of the network interfaces of your computer. Instead, they are connected to a virtual interface (meaning it only exists in software) calledlo. You can't connect to this address over the network (when you give somebody your address you can't just say "home"), but it is very useful for connecting to services that run on your local computer. For example to test a service that you are setting up, your browser can connect to it on this address.

Router

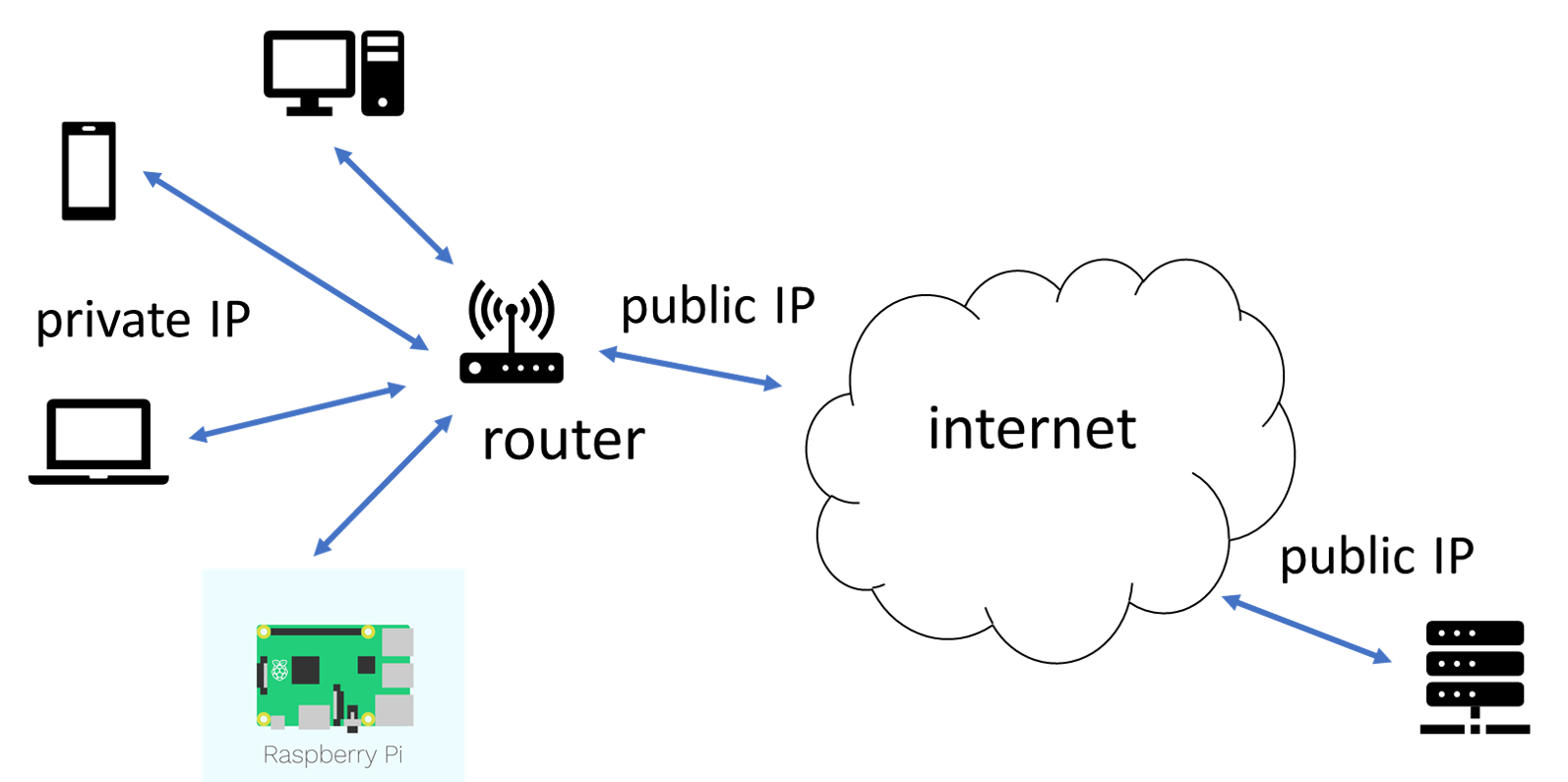

Now you may wonder: if my laptop's WiFi interface has a private address, how come I can go on the internet? Where is the public address? That brings us to another key component in the internet: the router. The router is a special device that takes care of connecting computers, either via Ethernet cables or WiFi. For a typical home network, the router will have one interface with a public IP address and one with a private IP address. It allows computers on the private network to access the internet. I can also allow computers on the internet to access computers on your private network, but to do that you'll have to configure the router because by default it will shield your private network.

[^2]

[^2]

Your public IP address

If you are using a device connected to the internet via a router, it always has a public address, and you can find it using your web browser by visiting a service like www.whatismyip.com.

However, most often this address is not fixed, so every time you connect to the internet you might get a different public IP address. We will see later on how you can set up a server when your IP address is not fixed.

Host names and domain names

IP addresses are hard to remember. Instead, you can give your computer a name, this is the host name. For example, out of the box your Raspberry Pi is called raspberrypi. You can think of this as the equivalent of a person's first name. This is OK for use on a private network (equivalent to a people in a family using first names). For official purposes, you also need a surname. For computers, this is called a domain name, for example the domain I use for my Raspberry Pis is called limited.systems. So if I have a Raspberry Pi with host name rpi then its full name is rpi.limited.systems. The technical term is fully qualified domain name but I will just call it full name.

Out of the box the domain that your Raspberry Pi uses is called local so its full name is raspberrypi.local; this is not an official domain, it only works on a private network.

The local IP address 127.0.0.1 is linked to the name localhost.

DNS: domain name service

If you want to run web service, you need an officially recognised domain name (e.g. I have the domain limited.systems). Because domain names are official, you have to buy them from an authority (e.g in the UK this is Nominet) via a web hosting provider. The US authority ICANN gives a good explanation of the process.

The Domain Name Service (DNS) is an internet mechanism that links the full names (e.g. rpi.limited.systems) to the IP addresses. This service is provided by the web hosting company where you bought your domain.

Most internet providers will assign a dynamic IP address to non-commercial internet users. This means that the address can change at any time. Linking a domain to a dynamic address is not practical because you would have to update the link every time it changes. Fortunately there are free internet services that do this for you: they can give you a domain if your IP address is not fixed, for example www.freemyip.com. Once you've created such a domain, you can link it to your own domain using the tools on the web site of your service provider.

Services, clients, servers and ports

This section explains the relationship between services, servers and clients and also explains how ports are used to identify services.

Service

I've used the term service a few times already. By service I mean that someone on the internet is doing some task for you when you request it. For example:

- Twitter and Facebook provide social media services

- A DNS service provides names for your IP addresses

- GitHub provides a revision-controlled repository for code and data

- DropBox provides a service for sharing documents

Server

The term server is used in two ways: it can be a computer that is used to provide services, or the software on that computer that provides a specific service. For example, your Rasberry Pi will be a server. And it will e.g. run a web server or a Pleroma server to provide specific services.

Client

A client is the software you use to access a service. For example, your web browser, the Instagram app on your phone and your email app are all clients.

Ports

If your Rasberry Pi has a single IP address or full name, how can we access a specific service that it provides? The answer is simple: every service will get a unique number (between 0 and 65535) called a port.

- The ports numbers for well-known services are officially defined, for example, unencrypted web services use port 80, encrypted web services use port 443, email uses port 25 and so on. These port numbers are in the range 0-1023.

- Port numbers in the range 1024-49151 are called registered; in practice they can be used by services that are not well know but need a fixed port.

- Port numbers in the range 49152–65535 are called dynamic or private, and unless you are programming a web service you would not encounter them.

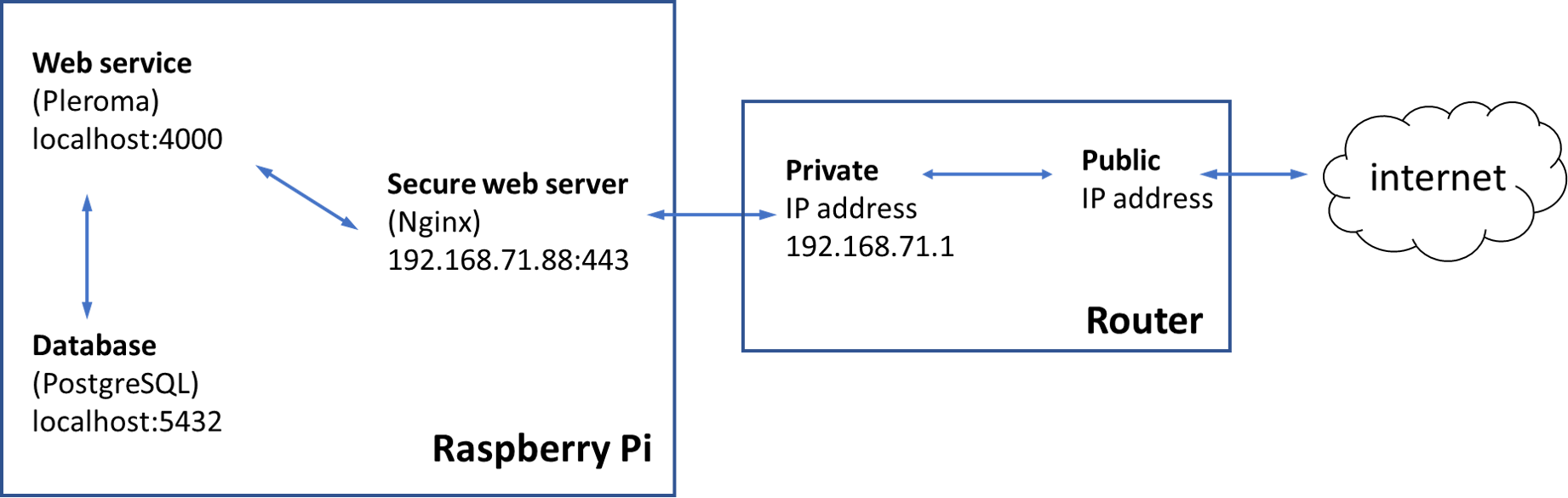

Most internet services today are web services. A typical scenario is to run a web service on your public domain on port 80 or 443. This web service talks via a local address to your own service, e.g. Pleroma, on a registered port, e.g. 4000. Usually your own service will talk to a database service, also on the local IP address, but on a different port, e.g. PostgreSQL uses port 5432. In this way, your own service and database are shielded from the internet.

Command line and terminal

Out of the box, when you start the Raspberry Pi it will present a graphical user interface (GUI). You can do many system administration tasks using this GUI but sooner or later you will need to use a different interface called a command line interface. To use this interface you start an application called a terminal. This terminal application simply provides you with a window where you can type commands, execute them and see the results. This command line interface is also called a shell. The Raspberry Pi runs Raspbian, which is a flavour of Linux. The shell it uses is called bash [^1].

A command typically consists of the name of a program to run together with additional information such as any files or other inputs this program should use. To execute a command you typed, hit RETURN; to edit it, you can use the left/right arrows and delete/backspace.

There are many many commands and ways to combine them, we will see more practical examples below. But let's look at a few simple examples:

man man

The command man (for manual) will display the manual for the command that comes after it (in this case also man). So this command will show you how to use man.

Another example: the command history will display a numbered list of your previous commands. You can then run the command again using this number. For example, the last two commands in my history are:

709 man man

710 history

If I want to run command 709 again, I can do !709. You can also browse through the history using up and down arrows.

Another very useful feature of the shell is autocompletion. For example suppose I want to use one of the develoment tools, such as a compiler. There are many of these and they have long names all starting with arm-linux. When I type in the shell arm-l and then hit TAB the shell will automatically expand this to:

wim@rpi:~ $ arm-linux-gnueabihf-

If I now hit TAB twice , I will get a list of all commands starting with arm-linux-gnueabihf-:

wim@rpi:~ $ arm-

arm-linux-gnueabihf-addr2line arm-linux-gnueabihf-g++-6 arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcov arm-linux-gnueabihf-ld.gold arm-linux-gnueabihf-python3m-config

arm-linux-gnueabihf-ar arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcov-6 arm-linux-gnueabihf-nm arm-linux-gnueabihf-python-config

arm-linux-gnueabihf-as arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc-6 arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcov-dump arm-linux-gnueabihf-objcopy arm-linux-gnueabihf-ranlib

arm-linux-gnueabihf-c++filt arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc-ar arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcov-dump-6 arm-linux-gnueabihf-objdump arm-linux-gnueabihf-readelf

arm-linux-gnueabihf-cpp arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc-ar-6 arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcov-tool arm-linux-gnueabihf-pkg-config arm-linux-gnueabihf-run

arm-linux-gnueabihf-cpp-6 arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc-nm arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcov-tool-6 arm-linux-gnueabihf-python2.7-config arm-linux-gnueabihf-size

arm-linux-gnueabihf-dwp arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc-nm-6 arm-linux-gnueabihf-gprof arm-linux-gnueabihf-python3.5-config arm-linux-gnueabihf-strings

arm-linux-gnueabihf-elfedit arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc-ranlib arm-linux-gnueabihf-ld arm-linux-gnueabihf-python3.5m-config arm-linux-gnueabihf-strip

arm-linux-gnueabihf-g++ arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc-ranlib-6 arm-linux-gnueabihf-ld.bfd arm-linux-gnueabihf-python3-config arm-unknown-linux-gnueabihf-pkg-config

Suppose what I need is the one of the GNU tools, I just type g and TAB twice to get a much shorter list:

wim@rpi:~ $ arm-linux-gnueabihf-g

arm-linux-gnueabihf-g++ arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc-ar arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc-ranlib arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcov-dump arm-linux-gnueabihf-gprof

arm-linux-gnueabihf-g++-6 arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc-ar-6 arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc-ranlib-6 arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcov-dump-6

arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc-nm arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcov arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcov-tool

arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc-6 arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcc-nm-6 arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcov-6 arm-linux-gnueabihf-gcov-tool-6

If the tool I need is gprof, then just typing p TAB will expand to the full command. This feature saves a lot of typing and reduces the chance of mistakes.

Remote access to the Raspberry Pi command line

Your Raspberry Pi can provide a service called sshd that allows you to access the command line from another computer using a client called ssh. You have to enable this feature as explained on the raspberrypi.org web site. If your computer runs Windows, you either need to install a separate program called PuTTY or (on Windows 10 or later) install the Ubuntu app which gives you a Linux terminal. On MacOS and Linux you can use the command-line client as follows:

ssh [email protected]

or

ssh username@ip-address

You will be prompted for a password and when this is accepted you get a command line on the Raspberry Pi.

Files and folders

In Linux, folders are traditionally called directories, and shortcuts to files or folders are called symbolic links. Nested folder names are separated with '/', and the folder that contains all other folders is just '/'. A shorthand for the current folder is '.', the folder that contains this folder is '..'. The full list of all nested folders from '/' up to the current folder is called the path.

There are many commands to work with files and folders, here are the most common ones:

-

pwd: print the path of the current folder -

ls: list the files in the current folder -

cd folder-path: "change directory", navigate to the folder path listed. To navigate to a folder in the current folder you can just use the name. -

mkdir folder-path: "make directory", create a folder -

mv: rename ("move") a file or folder -

cp: copy a file or folder -

rm: delete ("remove") a file -

rmdir: remove a directory. The directory must be empty.

To edit a file on command line on the Pi, the easiest way is to use the command editor name-of-the-file. It will open the file in an easy-to-use editor.

Two more very useful commands are find (to find a file in a folder) and grep (to find certain keywords or patterns in a file).

Have a look at the man pages for these commands as they come with many handy options.

File systems

A file system is a particular way to organise files on a storage medium (hard drive, SD card, pen drive ...). File systems have rather undescriptive names like VFAT, NTFS, ext4, HFS+, and many others. When you format a storage medium you choose the file system it will use. For this guide is is good to know that the micro-SD card on your Raspberry Pi is split into two parts (called partitions). The boot partition is formatted in VFAT format, this means that you can access this parition from a Windows, Mac or Linux computer. The root partition is formatted in ext4 which is a Linux-specific format, so this partition can't be accessed from a Windows or Mac computer. When you connect the micro-SD card to a Windows or Mac computer, you will only see the boot partition. This is not a problem, because there is usually no reason to access the root partition on another computer.

Users and permissions

This section explains the concepts of a user and superuser in Linux, and how they relate to permissions and privileges.

User and superuser

A user is an account on the system that comes with certain rights and restrictions and a dedicated folder, located in the /home folder and called home directory. Users can run applications, create files and access the network but they can only create and modify files and folders in their home directory.

There is a special user with the name root, called the root user or superuser, similar to the Administrator under Windows. This user can access all files and folders on the system, and it can create new user accounts and manage them.

Permissions and privileges

Every file and folder has a set of permissions determining who can do what to it. The permissions decide if a user can read, write and/or execute a file. The permissions apply to three levels: the first is the individual user, the second is a group of users, and the third level is everyone (also called "the world"). If you run the command ls -l you will see the permissions for each file and folder, e.g.:

-rw-r----- 1 wim authors 1479 Jan 28 16:44 raspberry-pi-admin-beginners-guide.md

In this example you see that there is a user wim which belongs to a group called authors and the permission on the file are:

- User

wimcan read and modify ("write") the file (rw-) - Any user in group

authorscan read the file (r--) - No other user can access the file (

---)

The third dash means that nobody can execute the file.

The first dash shows if it is a file or a directory, e.g. ls -l /home/ shows

drwxr-xr-x 1 wim wim 4096 Jan 11 14:30 wim

The d shows that wim is a folder; the other permissions mean that user wim can read and modify files in this folder, and all other users can read them; the x means that a user can access the folder.

or when you run ls -l /bin/ls you will see

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 133792 Jan 18 2018 /bin/ls

We see that the program /bin/ls is owned by user root in group root; any user can execute this program (x) and read the file, but only root can modify it.

To change permissions and ownership on a file, there are three commands: chmod to change permissions, chown to change the user who owns the file, and chgrp to change the group.

Superuser access

The superuser can give ordinary user superuser priviliges for some or all tasks by adding the user in the /etc/sudoers file. To edit this file, the superuser runs the command visudo. Once this is done, the ordinary user can run the commands with superuser access using the sudo command. This is in particular convenient to configure and control services. On a Linux system, the configuration files for services are stored in the folder /etc and can only be modified by root. For example, to change the host name, you'd need to use sudo:

sudo editor /etc/hostname

You should only use superuser access for tasks that really need it. The main tasks for which you need superuser access are:

- Creating and managing user accounts (using

useradd,userdel,usermod) and groups (groupadd,groupdel,groupmod) - Installing software (using

apt, see the next section) - Configuring services (by creating and editing configuration files in

/etc) - Setting up, running and stopping system services (using

systemctl, see section Setting up and running services)

In particular, you do not need superuser access to use git and to build software.

Installing software

Managing software packages

Most of the software to install on the Pi is available as a package stored in a repository on the internet. Each package contains a particular application or library (a piece of software that supports different applications) but most application depend on other applications and/or libraries to work correctly. To make sure that all packages on which an application depends get installed, with the correct versions, we use a package manager. A package manager keeps a database of your installed packages and also knows which packages are available on the internet in repositories. You can add additional repositories for software that is not available in the main repository.

On the Raspberry Pi, the package system is called apt and the command to manage package is also called apt. In other tutorials you will also see apt-get (similar to apt but older), aptitude (also similar but more interactive) and dpkg (very low level, rarely needed).

The first thing to do with a package management system is make sure the packages are up-to-date. With apt this means your run

apt update

to get the most recent list of packages, then you run

apt upgrade

to install them.

To install a new package you use

apt install package-name

Here is a list of the most used apt commands and their purpose:

apt installInstalls a packageapt removeremove Removes a packageapt purgeRemoves package with configurationapt updateRefreshes the list of packagesapt upgradeUpgrades all upgradable packagesapt autoremoveRemoves packages that are no longer neededapt full-upgradeUpgrades packages with auto-handling of dependenciesapt searchSearches for a given term in all packagesapt showShows package detailsapt listLists packages corresponding to given criteria (installed, upgradable, ...)apt edit-sourcesEdits list of repository sources

For more details, see Ubuntu's apt user guide or man apt.

Using git

Git is a version control system for software source code. It keeps track of changes to files so that you can roll back to an earlier version, and makes it easy to combine changes made by different people. For the purpose of installing software to run a service, e.g. Pleroma or Mastodon, the main use of git is to get a specific version of the source code from an internet repository such as GitHub or GitLab. You need only a few commands for that. For example, suppose you wanted to install Pleroma. To get the source using git you would do

git clone https://git.pleroma.social/pleroma/pleroma.git

You would do this only once. From then on, every time you want to update the source to get the latest version, you use

git pull

This is all you need to download source code with git. If you want to learn more, there is a free e-book, and of course there is man git.

Building software

Building software from source code is not particularly difficult. It always follows the same pattern:

- get the software

- read the installation documentation to learn about dependencies and configuration options

- get and install its dependencies

- configure the software

- build it

- test it

- run it

Build tools

Most modern software uses a build tool to control the process of building the application from source code. There are many different build tools. The oldest but still widely used one is called make. To build Mastodon you would use a tool called rake and to build Pleroma a tool called mix. All these tools have in common that they can do differnt tasks by using extra arguments (called targets or actions). For example, a typical use of make would be

make all

make test

make install

A more modern build tool like mix would handle tasks like downloading and building software dependencies as well, for example for Pleroma some of the steps are

mix dependencies.get

mix dependencies.compile

mix compile

mix test

Because the actions can be different for each application you want to build, the software documentation will explain the different tasks that the build tool should do, and when to do them.

Setting up and running services

When you have installed a service, you usually would like that it starts automatically whenever your Pi reboots. The mechanism used to configure, start and stop services is called systemd. Each service has a configuration file in /etc/systemd. To control the service (start, stop, get status etc) you use the command systemctl. For example, to start the nginx web server, you would do

sudo systemctl start nginx.service

This is one of the few occasions where you need root access when setting up a service: the /etc/systemd is only accessibly by root, and to control services you need to run systemctl as root.

The Raspberry Pi documentation gives a good explanation of how to create and manage a service with systemd.

Next steps

You are now ready to follow any tutorial for installing a service on your Raspberry Pi. For example have a look at my tutorial about installing Pleroma and Mastodon. Have fun!

[^1]: The name Bash is a pun. It stands for "Bourne Again SHell", because it replaced the older Bourne shell, named after Stephen Bourne who created it in 1979.

[^2]: Raspberry Pi drawing by diazchris