Week 03 Data Visualization - pointOfive/stat130chat130 GitHub Wiki

Populations and Sampling and more interesting EDA by making figures with AI ChatBots

Tutorial/Homework: Topics

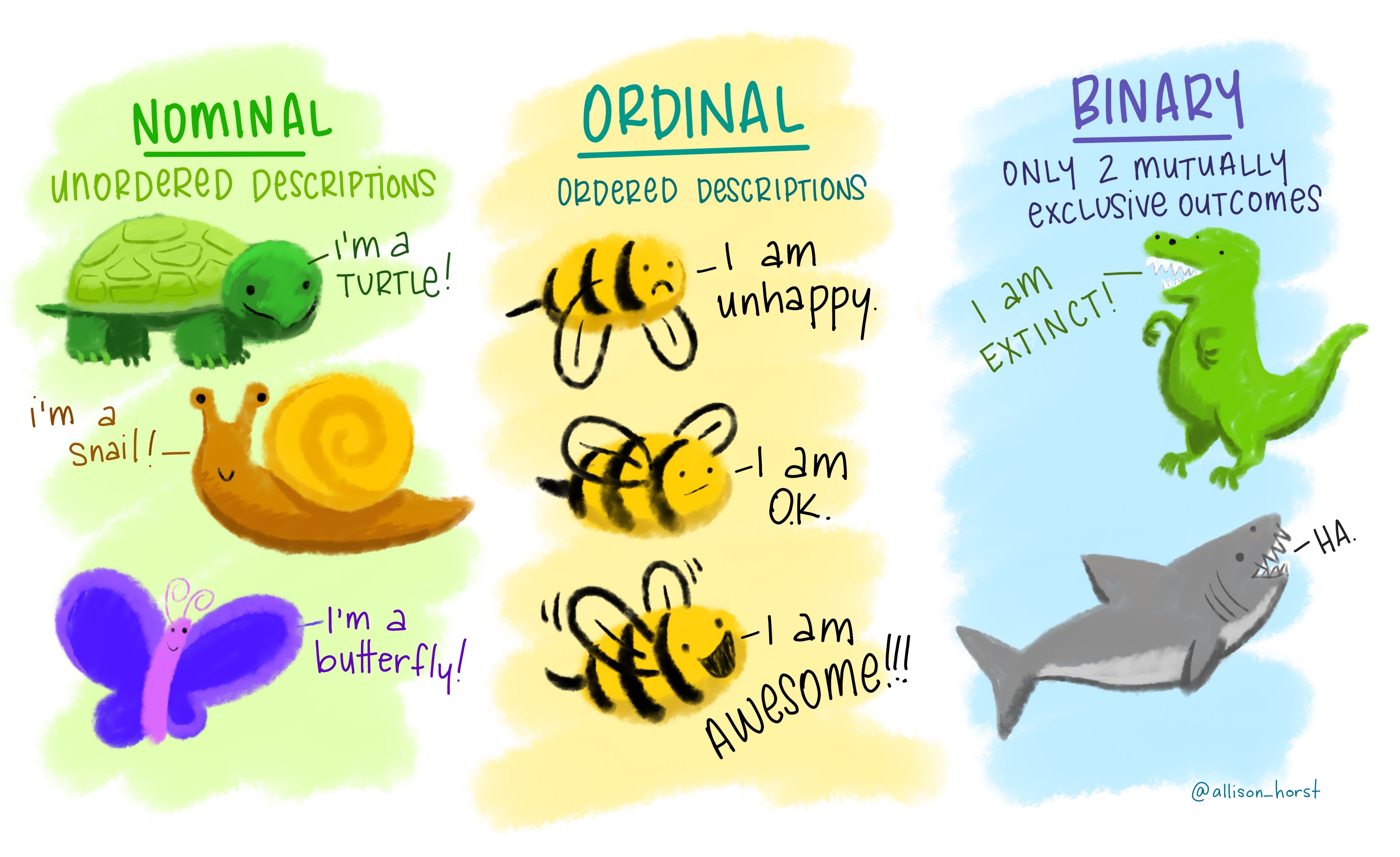

- More Precise Data Types (As Opposed to Object Types): continuous, discrete, nominal and ordinal categorical, and binary

- Bar Plots and Modes

- Histograms

- Box Plots, Range, IQR, and Outliers

- Skew and Multimodality

Tutorial/Homework: Lecture Extensions

These are topics introduced in the lecture that build upon the tutorial/homework topics discussed above

Topic numbers below correspond to extensions of topic items above.

2. Plotting: Plotly, Seaborn, Matplotlib, Pandas, and other visualization tools.

___ i. Legends, annotations, figure panels, etc.

3. Kernel Density Estimation using Violin Plots

5. Log Transformations

Lecture: New Topics

This section introduces new concepts that are not covered in the tutorial/homework topics.

- Populations from scipy import stats

stats.multinomialandnp.random.choice()stats.norm,stats.gamma, andstats.poisson

- Samples versus populations (distributions)

- Statistical Inference

Out of Scope

- Material covered in future weeks

- Anything not substantively addressed above

- Expectation, moments, integration, heavy tailed distributions

- Kernel functions for kernel density estimation

- bokeh, shiny, d3, etc...

Tutorial/Homework: Topics

Continuous, discrete, nominal and ordinal categorical, and binary

Not to be confused with type(), .astype(), and .dtypes; or, list, tuple, dict, str, and float and int (although the latter two correspond to continuous and discrete numerical variables...).

Bar Plots and Modes

A bar plot is a chart that presents categorical data with rectangular bars with heights (or lengths) proportional to the values that they represent.

import pandas as pd

import plotly.express as px

# Sample data

df = pd.DataFrame({

'Categories': ['Category1', 'Category2', 'Category3'],

'Values': [10, 20, 30]

})

# Create a bar plot with Plotly

fig = px.bar(df, x='Categories', y='Values', text='Values')

# The bars can be plotted horizontally instead of vertically by switching `x` and `y`

# Show the plot

fig.show()

A bar plot is essentially a visual representation of the .value_counts() method of the pandas library.

Remember, the

.value_counts()method produces counts of unique values, sorted in descending order starting with the most frequently occurring element. By default,.value_counts()excludes missing values, but you can include them using.value_counts(dropna=False).

# Example data

data = pd.Series(['a', 'b', 'a', 'c', 'b', 'a', 'd', 'a'], name="Variable")

# Count occurrences of each category

counts = data.value_counts()

# Create bar plot with Plotly

fig = px.bar(counts, y=counts.values, x=counts.index, text=counts.values)

# This updates the layout to add a title and labels to the x and y axes

fig.update_layout(title_text='Value Counts', xaxis_title='Categories', yaxis_title='Count')

# Show the plot

fig.show()

In this code, we first count the occurrences of each category in the series using .value_counts(). Then, we create a bar plot with px.bar(). The y argument is set to the counts (the number of occurrences of each category), and the x argument is set to the index of the counts (the categories themselves). The text argument is used to display the count numbers on top of the bars. For example, the height of the 'a' bar represents the count of 'a' in the dataset.

A bar plot is a simple yet effective way to understand the distribution of categorical data. It provides a clear visual alternative to reading

df.value_counts().

With interactive plotly bar plots, you can hover over the bars to see the exact counts, zoom in and out, and even save the plot as a PNG file.

The mode in statistics is the value (or values) that appears most frequently in a data set. In the bar plot above, 'a' is the mode since it appears most frequently in the dataset.

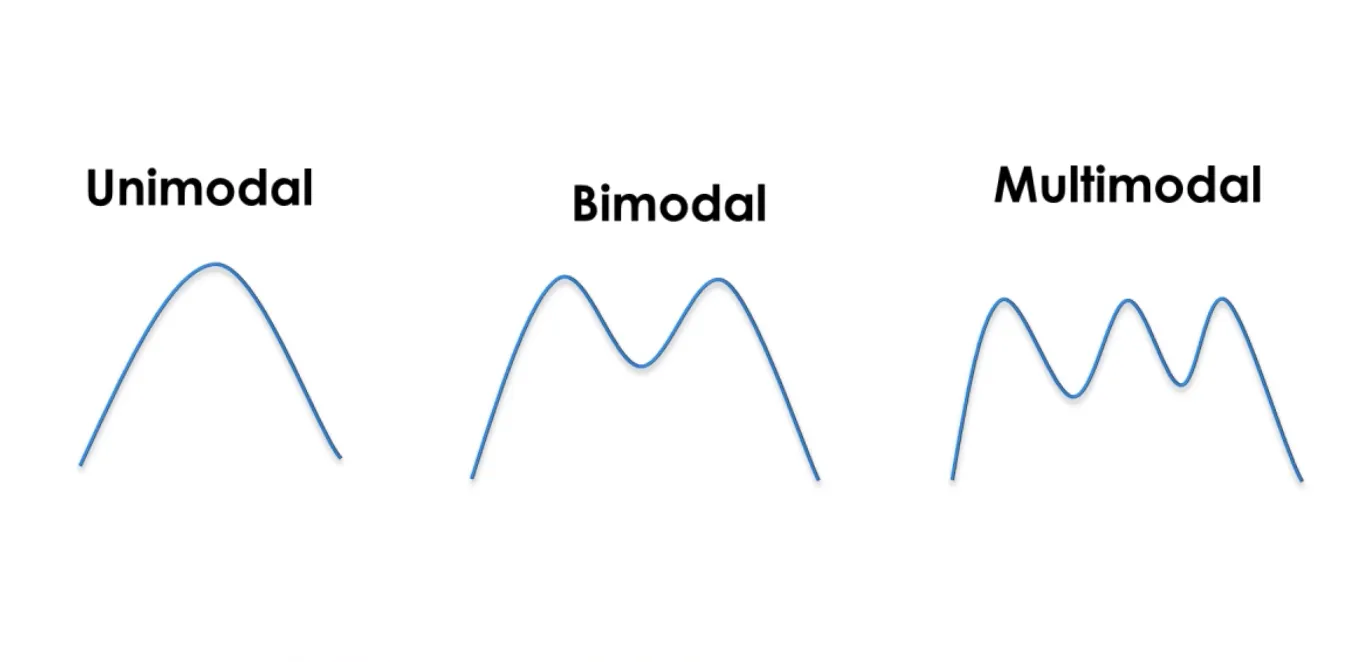

The term "modes" is also used to refer to "peaks" in a distribution of data, which will be discussed later in the context of multimodality.

Histograms

A histogram is a graphical display of data using bars of different heights. It is similar to a bar plot, but a histogram instead counts groups of numbers within ranges. That is, the height of each bar shows how many data points fall into each range. For example, if you measure the heights of trees in an orchard, you could put the heights data into intervals of 50 cm, so a tree that is 260 cm tall would be added to the "250-300" range. Histograms are a great way to show results of numeric data, such as weight, height, time, etc.

-

In a histogram, the width of the bars (also known as bins) represents the interval that is used to group the data points. The choice of bin size can greatly affect the resulting histogram and can change the way we interpret the data.

-

If the bin size is too large, each bar might span a wide range of values, which could obscure important details about how the data is distributed. On the other hand, if the bin size is too small, the histogram could become cluttered with many bars, making it difficult to see the overall pattern.

-

Choosing an appropriate bin size is a balance between accurately representing the data and maintaining readability.

To illustrate this, the code below generates two histograms for the same dataset, but with different bin sizes. The first histogram uses a smaller bin size, and the second one uses a larger bin size. As you can see, the histogram with the smaller bin size has more bars, each representing a narrower range of values. In contrast, the histogram with the larger bin size has fewer bars, each representing a wider range of values.

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

import plotly.graph_objects as go

# Generate a random dataset

np.random.seed(0) # Seed the random number generator for reproducibility

n = 500

data = stats.norm().rvs(size=n)

# Create a histogram with smaller bin size

fig1 = go.Figure(data=[go.Histogram(x=data, nbinsx=50)])

fig1.update_layout(title_text='Histogram with Smaller Bin Size')

fig1.show()

# Create a histogram with larger bin size

fig2 = go.Figure(data=[go.Histogram(x=data, nbinsx=10)])

fig2.update_layout(title_text='Histogram with Larger Bin Size')

fig2.show()

In

px.histogram(fromimport plotly.express as px), the parameter specifying the number of bins isnbins(notnbinsx); whereas, inseabornandmatplotlib(and hencepandas), the parameter is justbins. Here's some nifty code that lets you think about "widths" instead of the number of bins, which is probably more useful sometimes.

import math

bin_width = 0.5 # Choose your desired bin width

nbinsx = math.ceil((data.max() - data.min()) / bin_width) # or `nbins` or `bins` if you're using another library

- Also, please note that the actual bin width in the histogram might not be exactly the same as the desired bin width due to the way that

Plotlyautomatically calculates the bin edges.

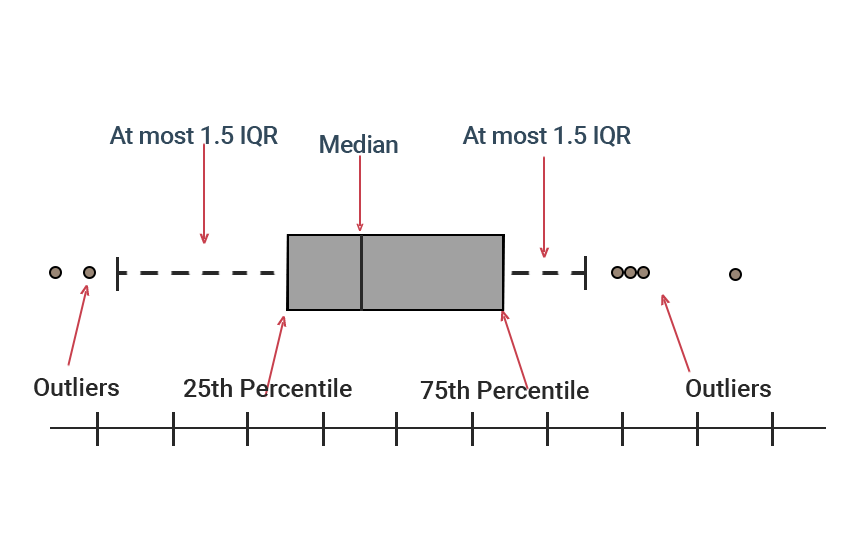

Box plots and spread

In statistics, the term range refers to the difference between the highest and lowest values in a dataset, so it provides a simple measure of the spread (or dispersion or variability) of the data. For example, in the set {4, 6, 9, 3, 7}, the lowest value is 3, and the highest is 9. So the range is 9 - 3 = 6.

The range can sometimes be misleading if the highest and lowest values are extremely exceptional relative to most of the values in the data set, so be careful when considering the range of a numeric variable. For example, the range of salaries is not very representative of most "working class" salaries.

The interquartile range (IQR) is another statistical measure of the spread (or dispersion or variability) of the data. It is defined as the difference between the 75th and 25th percentiles of the data. In other words, the IQR includes the 50% of data points that are above the first and third quartiles (Q1 and Q3). The IQR is used to assess the variability where most of your values lie. Larger values indicate that the central portion of your data spread out further, while smaller values show that the middle values cluster more tightly.

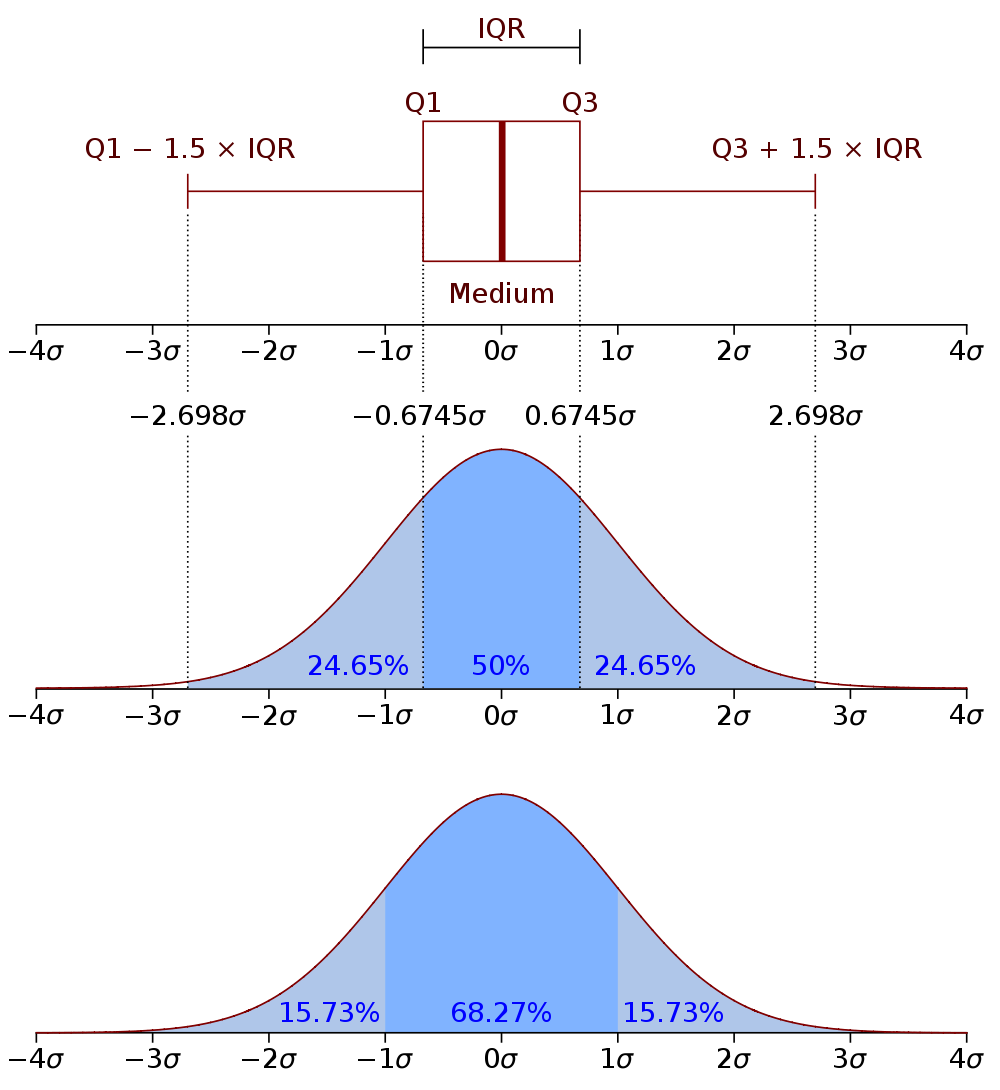

A box plot is a graphical representation for characterizing the relative statistical spread (or dispersion or variability) of a numerical data distribution around its median. A box plot serves a similar purpose to as histogram, but it is a simpler alternative that provides a higher-level summary of numerical data.

The "box" of a box plot is constructed out of the first (Q1) and third quartiles (Q3) separated by the median (which is the second quartile Q2); so, a box plot shows the the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile with the "box" containing the middle 50% of the data.

Box plots additionally draw whiskers (lines extending from the box) which typically extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR) of the first and third quartiles.

- The lower whisker extends to the smallest data point within 1.5 * IQR below the first quartile.

- The upper whisker extends to the largest data point within 1.5 * IQR above the third quartile.

Data points that fall outside this range of the whiskers are typically termed outliers and are plotted as individual points.

The term "outliers" is only meant to be suggestive as outliers can mean different things in different context. In the context of a box plot, referring to the points beyond the extent of the whiskers is simply a technical term related to the definitional construction of a box plot.

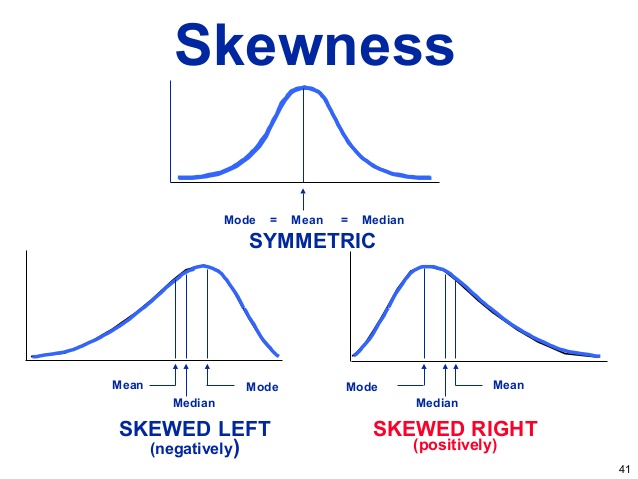

Skew and Multimodality

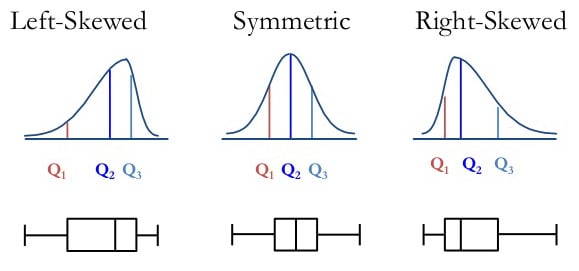

Skewness is a measure of the asymmetry of a data distribution. If skewness is present, then it's either left "negative" or right "positive" skew.

- If the data is spread out more to the left direction then the skew is "negative"

- If the data is spread out more to the right direction then the skew is "positive"

Skewness can be understood in terms of its affect on the relationship between the mean and median.

- The mean is the average of all data points in the dataset.

- The median is the middle point of a number set, in which half the numbers are above the median and half are below.

The median is the 50th percentile of the data so it is the "second quartile" and can be denoted as Q2, similarly to the first and third quartiles Q1 and Q3 (which are the 25th and 75th percentile of the data).

In a symmetric distribution, the mean and median are the same. However, when data is skewed, the mean and median will differ.

- In a positive skew context, the mean will be greater than the median. This is because the mean is influenced by the high values in the tail of the distribution and gets pulled in the direction of the skew.

- In a negative skew context, the mean will be less than the median. This is because the mean is influenced by the low values in the tail of the distribution and gets pulled in the direction of the skew.

A simple way to remember this relationship is that the mean is 'pulled' in the direction of the skew.

Modality refers to the general natures of the "peaks" that may be present in a numerical data set.

These "peaks" are often informally referred to as "modes" but these should not be confused with the technical definition of mode which refers to the most common unique value in a data set.

Box plots are great for comparing the distributions of different groups of data, and they clearly indicate the presence of skew in a numerical data set. However, be careful, as box plots cannot represent multimodality in a data set, and they do not indicate the amount of data they represent without the addition of explicit annotations indicating this. Histograms, on the other hand, automatically give indications of both modality and sample size (through their "y-axis").

Normal Distributions

An interesting "special case" of unimodal distributions is the normal distribution. The figures below illustrate the quantiles (Q1 and Q3) for a normal distribution based on the corresponding boxplot. The "sigma" (σ) character in the figure below signifies the standard deviation, and the bottom-most figure shows the percentiles that correspond to different multiplicative ranges of the standard deviation.

In statistics a normal distribution is a fundamental concept that describes how data points are spread out. It is also known as the Gaussian distribution, named after the mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss. The normal distribution is essential because it often appears in real-world data and underpins many statistical methods.

The standard deviation is essentially defined specifically for normal distributions and its meaning is exactly clear in the context of normal distributions. The further a distribution deviates from "normality" (i.e., the more "non-normal" it is), the harder it becomes to interpret the standard deviation. The greater the degree that a data distribution is skewed or non unimodal, the less clear it is what the meaning of the standard deviation is.

Characteristics of a Normal Distribution

A normal distribution has several key features:

- Symmetry: The distribution is perfectly symmetric about its mean "mu" (μ).

- Central Tendency: The mean, median, and mode of the distribution are all equal and located at the center of the distribution.

- Bell-Shaped Curve: The distribution forms a bell-shaped curve, with the highest point at the mean.

- Spread: The spread of the distribution is determined by the standard deviation. A larger standard deviation means the data is more spread out from the mean, while a smaller standard deviation means the data is more clustered around the mean.

- Known Probabilities: About two-thirds of the area of a normal distribution is within "plus and minus ONE standard deviation of the mean," while about 95% of the area of a normal distribution is within "plus and minus TWO standard deviations of the mean."

Tutorial/Homework: Lecture Extensions

Modern Plotting

There are many data visualization libraries, and modern ChatBots are very familiar with them. Making data visualizations is therefore just a matter of being aware of what's available in different visualization libraries and requesting the code to accomplish your objectives from ChatBots. Learning what's possible and available in different visualization libraries is just a matter of keeping your eyes open to see what's possible. All you need to do to become an expert in data visualization is to start exploring data visualization "galleries" (like those of plotly, seaborn, which is built on matplotlib which pandas provides direct access to, and bokeh, ggplot, shiny, or D3.js, and other data visualization compilation galleries (like this one for python or this one for R since exploring types of possible data visualization is truly a language agnostic question).

We've chosen to emphasize plotly because it's a popular and attractive data visualization library that provides the most modern features that one would like from a visualization library, such as information panel access via "hovering" and rudimentary "interactive data dashboarding" and animation. But you're welcome to work in whatever tools you like, with the only caveat being that not all types of figures render on GitHub (so TAs marking your homework submissions can see your figures), especially the fancier, more complicated kinds of figures which are essentially some form of javascript "widget". For example, unless you use fig.show(renderer="png") for all plotly figures that are part of GitHub (and MarkUs) submissions, the plotly figure will simply not appear on rendered GitHub (or MarkUs) pages.

The foundations of data visualization have been considered and studied for a long time, e.g., following the seminal work of Edward Tufte and popularized through mainstream treatments such as How to Lie with Statistics (which, contrary to the apparent sentiment of the title, actually instead tries to educate the general population about how to be literate and think critically about data visualization). We've come very far since those "early days," however, and modern taxonomies and organizational characterizations of visualization, such as those from David McCandless are much more focused on optimizing the power of informative storytelling through data visualization. David McCandless is a new breed of Data Journalists who report on the world empirically, using data visualizations, but not in an old, dry, boring way. They make looking at data fun and engaging. My favorite Data Journalism comes from The Pudding, which makes reading a news article a crazy, interactive, immersive experience. To make the kinds of awesome "knock your socks off" data visualizations that we're seeing from Data Journalists these days requires the previously mentioned D3.js. If you haven't figured it out, the ".js" stands for javascript. But as you may have figured out, with the advent of ChatBots, that's not going to matter. You can work with a ChatBot to make awesome data visualizations with D3.js. While we won't be formally doing this as part of STA130, the only thing stopping you from doing so is... you. And your good excuses and explanations for why this currently is so (which do not include "I can't code in javascript or D3.js").

Legends, annotations, figure panels, etc.

There are many standard components, elements, and ornaments available for data visualization plots. The three listed above—legends, annotations, and figure panels—are some basic "standard" aspects often leveraged in data visualization. But the more examples of data visualizations you see, the more familiar you'll become with the nature of the canvas and the availability of tools at your disposal for data visualization purposes. If you're not familiar with legends, annotations, and figure panels, the homework and lectures will introduce you to these topics, and over time you'll become increasingly comfortable incorporating these kinds of elements into your data visualizations. At that point, you'll simply be asking a ChatBot to provide the necessary code to execute the plans you've envisioned for your figure. Additionally, the vision you've decided upon might be dynamically evolved, updated, and improved through an interactive process with a ChatBot. ChatBots can be very good soundboards for exploring ideas and suggesting possible variations and extensions relative to what you're currently attempting to do.

Most of the figures made below were created in exactly this manner. Have a look at how Prof. Schwartz interacts with a ChatBot to produce figures. All you need to know to be able to do this is what you want to see in the figure, which is exactly what that transcript log demonstrates.

Smoothed Histograms

The previously introduced histograms (and box plots, etc.) provide a simple way to understand the empirical distribution of data though simple visualization that reflects the location (central tendency) and spread (scale) of the data. The choice of the number of bins to use for a histogram is, in some sense, arbitrary, but can be sensibly made. For example, plotly histograms determine a number of bins approximately matching the number you specify. The number of bins only matters significantly when comparing, say, 5 bins versus 25 bins or 100 bins because this impacts how coarsely the histogram represents the data. These differences change the degree of "data compression" and "simplification" presented to the viewer, whereas changes of "plus or minus a few bins" won't qualitatively affect the information presented.

It can nonetheless feel a little jarring that histograms can indeed start to look different if the bins get moved a little to left or to the right, or if "plus or minus a few bins". This makes it feel like histograms have some degree of "arbitrariness" to them (which they do). One might then wonder if there was a way to remove the "artifacts" caused by the exact details of the binning specifications. And, indeed, there is a "continuous" approach to remove the "discrete" nature of histograms caused by their binning mechanism called kernel density estimation (KDE). A KDE is essentially a "local average of the number of points" (within each local area of the data). While histograms provide a discretely binned approximation of empirical distribution of data, a KDE can represent the approximation of empirical distribution of data as a smooth curved function.

import plotly.express as px

# Create a violin plot

df = px.data.tips()

fig = px.violin(df[df.day=='Sat'], y="total_bill", x="day", color="sex",

box=True, points="all", hover_data=df.columns)

fig.show()

Most plotting libraries, like plotly, provide access to kernel density estimation (KDE) through a so-called violin plot. The plotly library also provides an alternative interface to this functionality through ff.create_distplot although this is no longer preferred and is now depreciated. Nonetheless the following code and visualization is still informative since it shows that the violin plot is just mirrored image reflection of a KDE.

import plotly.figure_factory as ff

# Separate data for each sex

df_saturday = df[df['day'] == 'Sat']

male_bills = df_saturday[df_saturday['sex'] == 'Male']['total_bill']

female_bills = df_saturday[df_saturday['sex'] == 'Female']['total_bill']

fig = ff.create_distplot([male_bills, female_bills],

group_labels=['Male', 'Female'],

show_hist=False, show_rug=True)

fig.update_layout(title='KDE Plot of Total Bill on Saturday by Sex',

xaxis_title='Total Bill', yaxis_title='Density')

fig.show()

To see this even more explicitly, here we make a violin plot like the first one we made, but rather than making two different violin plots by sex we instead make a single violin plot where the KDE on each "side" of the violin plot is for either of the two levels of sex considered in our dataset.

import plotly.graph_objects as go

fig = go.Figure()

# Add Male distribution on the left side of the violin with a teal color

fig.add_trace(go.Violin(y=df_saturday['total_bill'][df_saturday['sex'] == 'Male'],

x=df_saturday['day'][df_saturday['sex'] == 'Male'],

side='negative', # Plots on the left side

line_color='teal', fillcolor='rgba(56, 108, 176, 0.6)',

name='Male', box_visible=True,

points='all', meanline_visible=True))

# Add Female distribution on the right side of the violin with a coral color

fig.add_trace(go.Violin(y=df_saturday['total_bill'][df_saturday['sex'] == 'Female'],

x=df_saturday['day'][df_saturday['sex'] == 'Female'],

side='positive', # Plots on the right side

line_color='coral', fillcolor='rgba(244, 114, 114, 0.6)',

name='Female', box_visible=True,

points='all', meanline_visible=True))

fig.update_layout(title='Total Bill Distribution on Saturday by Sex (Single Violin)',

yaxis_title='Total Bill', xaxis_title='Day', violinmode='overlay')

fig.show()

The nice thing about KDEs is that they give us a "histogram" but it doesn't have bins and is instead just a smooth curved function approximation of empirical distribution of data. Technically speaking, a KDE is a non-parametric estimation of the probability density function (PDF) of a continuous random variable. It is useful for visualizing the distribution of a dataset when we want a smooth curve, rather than a binned representation like a histogram.

In a KDE plot, each data point is replaced by a smooth, symmetric kernel (often Gaussian) centered at that point. Each kernel is given an "area" of 1/n (where n is the number of samples) and the sum of these kernels across all data points then produces a smooth curve that represents the estimated probability density underlying the data. It is the smooth curved function approximation of empirical distribution of data. A violin plot takes KDEs one step further by representing this in a visually pleasing manner. Unlike box plots, which display summary statistics (median, quartiles, etc.), violin plots show the entire distribution by mirroring the KDE on both sides of the axis, giving the plot its characteristic "violin" shape. Or, as demonstrated above, each side of the violin plot can represent two sides of a dichotomous division of the data.

A violin plot is especially useful for comparing distributions across different categories and displaying multi-modal distributions which a box plot would be unable to visualize. Visually examining an empirical data distribution is often more informative than just examining summary statistics, and a violin plot is often more aesthetically pleasing than a histogram while providing the same level of information and detail.

fig = go.Figure()

# Loop over unique days to add traces

for day in df['day'].unique():

# Male distribution

male_subset = df[(df['day'] == day) & (df['sex'] == 'Male')]

fig.add_trace(

go.Violin(y=male_subset['total_bill'],

x=[day] * len(male_subset), # x is the day for all entries

side='negative', # Left for Male

line_color='teal', fillcolor='rgba(56, 108, 176, 0.6)',

name='Male', box_visible=True, points='all', meanline_visible=True))

# Female distribution

female_subset = df[(df['day'] == day) & (df['sex'] == 'Female')]

fig.add_trace(

go.Violin(y=female_subset['total_bill'],

x=[day] * len(female_subset), # x is the day for all entries

side='positive', # Right for Female

line_color='coral', fillcolor='rgba(244, 114, 114, 0.6)',

name='Female', box_visible=True, points='all', meanline_visible=True))

fig.update_layout(title='Total Bill Distribution by Day and Sex',

yaxis_title='Total Bill', xaxis_title='Day', violinmode='overlay')

fig.show()

A plotly violin plot is an excellent choice when you want both a clear picture of the empirical data distribution and the ability to compare between different categories, while also enjoying the interactive benefits that plotly provides.

import seaborn as sns

df = sns.load_dataset('penguins').dropna() # Load the penguins dataset

fig = go.Figure()

fig = px.violin(df, y="bill_length_mm",

box=True, points="all", hover_data=df.columns)

fig.show()

Since a violin plot using a KDE presents the same information as a histogram but with a smoother representation, it turns out it has a similar "arbitrariness" issue as the choice of the number of bins in a histogram. This "artifact" comes from the choice of the kernel itself, but especially the bandwidth parameter, which inevitably controls the "width" of the kernel used to construct the KDE. So, if each data point becomes a mini Gaussian-shaped mound and all these mounds have "area" $\frac{1}{n}$ and are "added together" to produce the over all smooth curve function approximating the empirical data distribution (as shown in the linked image -- not the plotly code figures -- above), then the "width" of the kernel (and other details about the "arbitrary" choice of the kernel function) will affect how smoothed out the curve function of the KDE will be.

The bandwidth parameter in a KDE is similar to the number of bins in a histogram. More bins in a histogram create a finer, more detailed visual summary of the data, which corresponds to using a narrower bandwidth in KDE. This allows for a more sensitive estimate, capturing more details of the data’s structure, such as multimodality. On the other hand, fewer bins in a histogram result in a coarser, more simplified summary of the data, which is analogous to using a wider bandwidth in KDE.

Both the bandwidth in KDE and the number of bins in a histogram determine how granular or smooth the data representation will be. A narrower bandwidth (or more bins) can reveal intricate details, but it might also make the data appear overly complex, just as having too many bins in a histogram can. This complexity can make it difficult to grasp the overall pattern or trend in the data. Conversely, a wider bandwidth (or fewer bins) provides a smoother, more generalized view, but it risks oversimplifying the data, potentially missing important features.

Finding the right balance between detail and smoothness is key. Too few bins or too wide a bandwidth might oversimplify the data, while too many bins or too narrow a bandwidth might make the data appear overly complicated. The goal is to choose a setting that appropriately summarizes the data while still providing a clear and informative visual representation.

Log Transformations

When data is extremely right-skewed we can do a log transformation to allow us to work with the data on a more "normal" scale.

import numpy as np

from plotly.subplots import make_subplots

url = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/nsethi31/Kaggle-Data-Credit-Card-Fraud-Detection/master/creditcard.csv"

df = pd.read_csv(url)

# Log transformation of the amount column

df['log_amount'] = np.log(df['Amount'] + 1)

# Downsample the non-fraudulent class to 10,000 samples

non_fraudulent = df[df['Class'] == 0].sample(n=10000, random_state=42)

fraudulent = df[df['Class'] == 1]

# Combine the downsampled non-fraudulent class with the full fraudulent class

balanced_df = pd.concat([non_fraudulent, fraudulent])

# Calculate mean and standard deviation for original and log-transformed amounts

mean_amount = balanced_df['Amount'].mean()

std_amount = balanced_df['Amount'].std()

mean_log_amount = balanced_df['log_amount'].mean()

std_log_amount = balanced_df['log_amount'].std()

# Create subplots

fig = make_subplots(rows=1, cols=2, subplot_titles=("Original Amount", "Log Transformed Amount"))

# Define positions for Non-Fraudulent and Fraudulent with increased separation

positions = balanced_df['Class'].map({0: -0.6, 1: 0.6}) # Increased separation

# Left violin plot for original amount (red for fraud)

fig.add_trace(go.Violin(

y=balanced_df['Amount'][balanced_df['Class'] == 1],

x=[0.6]*len(balanced_df['Amount'][balanced_df['Class'] == 1]),

side='positive', line_color='red', fillcolor='rgba(244, 114, 114, 0.5)',

name='Fraud', box_visible=True, points='all', meanline_visible=True,

pointpos=-0.8, width=1.0, marker=dict(color='red', opacity=0.2)), row=1, col=1)

# Add a single trace for non-fraudulent transactions (purple)

fig.add_trace(go.Violin(

y=balanced_df['Amount'][balanced_df['Class'] == 0],

x=[-0.6]*len(balanced_df['Amount'][balanced_df['Class'] == 0]),

side='positive', line_color='purple', fillcolor='rgba(128, 0, 128, 0.5)',

name='Non-Fraud', box_visible=True, points='all', meanline_visible=True,

pointpos=-0.8, width=1.0, marker=dict(color='purple', opacity=0.2)), row=1, col=1)

# Right violin plot for log-transformed amount (blue for fraud)

fig.add_trace(go.Violin(

y=balanced_df['log_amount'][balanced_df['Class'] == 1],

x=[0.6]*len(balanced_df['log_amount'][balanced_df['Class'] == 1]),

side='positive', line_color='blue', fillcolor='rgba(56, 108, 176, 0.5)',

name='Fraud Log', box_visible=True, points='all', meanline_visible=True,

pointpos=-0.8, width=1.0, marker=dict(color='blue', opacity=0.2)), row=1, col=2)

# Add a single trace for non-fraudulent transactions (green)

fig.add_trace(go.Violin(

y=balanced_df['log_amount'][balanced_df['Class'] == 0],

x=[-0.6]*len(balanced_df['log_amount'][balanced_df['Class'] == 0]),

side='positive', line_color='green', fillcolor='rgba(0, 128, 0, 0.5)',

name='Non-Fraud Log', box_visible=True, points='all', meanline_visible=True,

pointpos=-0.8, width=1.0, marker=dict(color='green', opacity=0.2)), row=1, col=2)

# Add rectangles for mean and mean + 1 std in the original scale (narrowed width)

fig.add_shape(type='rect',x0=-.75, x1=-0.25, row=1, col=1,

y0=mean_amount, y1=mean_amount + std_amount,

fillcolor='rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.5)', line=dict(color='yellow', width=3))

# Add rectangles for mean and mean + 1 std in the log-transformed scale (narrowed width)

fig.add_shape(type='rect', x0=-.75, x1=-0.25, row=1, col=2,

y0=mean_log_amount, y1=mean_log_amount + std_log_amount,

fillcolor='rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.5)', line=dict(color='yellow', width=3))

# Add a box trace for mean ± std explanation to the legend

fig.add_trace(

go.Box(y=[None], # No data, just to create a legend entry

name='Mean ± Std', marker=dict(color='yellow'), line=dict(width=3)))

# Update layout

fig.update_layout(title='Transaction Amount Distribution: Original vs Log Transformed',

yaxis_title='Amount', yaxis2_title='Log Amount')

# Set x-axis limits for both panels

fig.update_xaxes(range=[-1.3, 1.3], title_text='Class', row=1, col=1)

fig.update_xaxes(range=[-1.3, 1.3], title_text='Class', row=1, col=2)

# Update x-axis ticks and add labels

fig.update_xaxes(tickvals=[-1, 1], ticktext=['Non-Fraud', 'Fraud'], row=1, col=1)

fig.update_xaxes(tickvals=[-1, 1], ticktext=['Non-Fraud', 'Fraud'], row=1, col=2)

fig.update_yaxes(range=[0, balanced_df['Amount'].max() + 500], row=1, col=1) # Adjust as needed

fig.show()

By log transforming the data in this example we're trying to make it look more like a normal distribution. This is because a normal distribution is simple and easy to think about in terms of its population parameters. That's just basically "the middle" location where the normal distribution is placed, and we can also interpret what the population standard deviation parameter indicates. Namely, for a population that's normally distributed about 95% of the area of the distribution* is between "plus and minus two standard deviations. We should careful here to distinguish between the sample mean statistic and the population mean parameter, and as well to distinguish between the sample standard deviation statistic and the population standard deviation parameter. But they carry the same meaning and interpretation if we're talking about an empirical distribution or a population distribution so long as their shape is approximately normally distributed.

The standard deviation of a right-skewed sample of data is hard to interpret because this really depends on the nature of the outliers and "decay behavior" of the tail (how quickly the data "peters out" to the right). The sample mean itself can also be very challenging to interpret because how far the mean is pulled away from the median depends on the degree of right-skew (and again the outliers) that are present in the data. So, when we encounter a dataset with right-skewed distribution having a majority of values are clustered at the lower end with a long tail extending towards higher values, this can make statistical analyses and interpretations challenging, especially for statistics like the mean and standard deviation. This can all be fixed, though, if we work on the log scale based on using a log transformation. This can make the data literally look more "normal" and approximately have the normal distribution "shape". We'll not discuss the mathematical operation that a log transformation executes, but the benefits of a log transformation are to (a) reduce right-skewness because the log transformation pulls he long tail of larger values is pulled closer to the bulk of smaller values and (b) make the meaning of statistics like the mean and standard deviation more interpretable (although we must remember that these only apply to the "log scale" that we're now working on as a result of the log transformation). After a log transformation the sample mean is a better representation of the central tendency, as it is less influenced by outliers and right-skew, and the standard deviation can be meaningfully understood in terms of what its interpretation regarding the spread of the data around the sample mean. The log transformation is a powerful technique for handling right-skewed data since by transforming the data to achieve a more approximately normal distribution shape we enhance our ability to interpret and have a more meaningful understanding of the dataset.

Lecture: New Topics

Populations and Distributions

A population is generally a theoretical idea that imagines the collection of all possible values the observations made for a random variable could hypothetically be. It can refer to concrete group, such as "All Canadians" or "All UofT Students" or "All UofT International Students"; but, for all but very small populations, it would for all practical purposes not be possible to actually measure every observation in a population that could possibly occur.

In Statistics, we often imagine a theoretical population as an idealized group of "all possible data points", and we represent these using a mathematical model called a distribution. We have already seen several of these distributions.

# The first we saw was the Multinomial distribution

from scipy import stats

number_to_select = 5 # n = 5

option_frequency = [0.6,0.3,0.1] # k = 3 options

Multinomial_distribution_object = stats.multinomial(n=number_to_select, p=option_frequency)

# Two special cases of the Multinomial distribution where there are just two options are

# - The Binomial distribution

p = 0.5 # chance of getting a success ("1" as opposed to "0") <- doesn't need to be 0.5

Binomial_distribution_object = stats.binom(n=number_to_select, p=p) # stats.multinomial(n=number_to_select, p=[p,1-p])

# - The Bernoulli distribution

Bernoulli_distribution_object = stats.bernoulli(p=p) # stats.binom(n=1, p=p)

# Some other distributions are the Normal, Poisson, and Gamma distributions

μ = 0 # mean parameter

σ = 1 # standard deviation parameter

Normal_distribution_object = stats.norm(loc=μ, scale=σ)

λ = 1 # mean-variance parameter

Poisson_distribution_object = stats.poisson(loc=λ)

α # shape parameter

θ # scale parameter

Gamma_distribution_object = stats.gamma(a=α, scale=θ)

Sampling

In Statistics, sampling refers to the process of selecting a subset of individuals from a population. Ideally, the sample should be collected in such a way that it is representative of the population. This is because the primary purpose of sampling is to estimate the characteristics (called parameters) of the whole population when it is impractical or impossible to collect data from an entire population. Estimating population parameters based on a sample is called statistical inference.

Do you recall the notion of statistical independence? This is very important here. When we're collecting samples from a population it will be most efficient if selecting one individual observation doesn't affect which of the other individual observations. If the samples are statistically dependent it means they come in clusters, like if selecting one person for the sample then means we'll also select all their friends for the sample. This is statistical dependence and perhaps you can see the problem here. This clustering in the sampling is going to make it more challenging to collect a sample that is more representative of the population. What actually happens when you have $n$ dependent rather than independent samples is that you don't really actually have $n$ independent pieces of information. Because the samples are dependent it's like each of the dependent samples is not quite a full piece of information. So with dependent sampling you may have $n$ samples but you don't have $n$ independent pieces of information. So that's why independent samples are preferred over $n$ dependent samples. Additionally, most statistical inference methods assume that the samples they're using are independent samples. So if this is not true and actually dependent samples are being used, then the statistical inference method will be overly confident and biased. All of the sampling demonstrated below is based on drawing independent samples from the distributions being sampled from.

# Samples can be taken from the Multinomial distributions (and special cases) in the code above

# using the "random variable samples" `.rvs(size=number_of_repetitions)` method of the distribution objects

Multinomial_distribution_object.rvs(size=1) # `number_of_repetitions` is many times "5 things are chosen from 3 options with `option_frequency`"

Binomial_distribution_object.rvs(size=1) # `number_of_repetitions` sets how many times "5 things are chosen from 2 options with chance `p`"

Bernoulli_distribution_object.rvs(size=1) # choose 0 or 1 with probability p

# Which can also be correspondingly created using the following

np.random.choice([0,1,2], p=option_frequency, size=number_to_select, replace=True)

np.random.choice([0,1], p=[p,1-p], size=number_to_select, replace=True)

np.random.choice([0,1], p=[p,1-p], size=1, replace=True) # Bernoulli

# And this is analogously done for the Normal, Poisson, and Gamma distributions objects

Normal_distribution_object.rvs(size=n) # `number_of_repetitions` sets how many "draws" we "sample" from this distribution

Poisson_distribution_object.rvs(size=n) # ditto

Gamma_distribution_object.rvs(size=n) # ditto

The $n$ samples from any of the above calls would typically be notated as $x_1, x_2, \cdots, x_n$.

Statistics Estimate Parameters

The Greek letters above (μ, σ, λ, α, and θ) are the parameters of their corresponding distributions. Parameters are the characteristics of population which we are trying to estimate by sampling. To make inferences on the population parameters, we estimate the parameter values with appropriately constructed statistics (which are mathematical functions of) samples. For example:

-

The population mean of a Normal distribution μ is estimated by the sample mean

$$\bar x = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{n=1}^n x_i$$

-

The population standard deviation of a normal distribution σ is estimated by the sample standard deviation

$$s = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n-1}\sum_{n=1}^n (x_i-\bar x)^2}$$

-

The population mean of a Poisson distribution λ (which is also the variance poisson distribution population) is estimated by the sample mean $\bar x$ or the sample variance $s^2$

-

And the shape α and scale θ parameters of a Gamma distribution can also be estimated, but the statistics for estimating these are a little more complicated than the examples above

Here we use the sample mean and sample standard deviation to estimate the normal distribution which best approximates the log transformed Amount data from the creditcard.csv dataset introduced above.

from scipy import stats

url = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/nsethi31/Kaggle-Data-Credit-Card-Fraud-Detection/master/creditcard.csv"

df = pd.read_csv(url)

# Log transformation of the amount column

df['log_amount'] = np.log(df['Amount'] + 1)

mean_log_amount = df['log_amount'].mean()

std_log_amount = df['log_amount'].std()

fig = go.Figure()

fig.add_trace(

go.Histogram(x=hist_data, nbinsx=30, histnorm='probability density',

name='Log Transformed Amount', opacity=0.6, marker_color='blue'))

# Create a range of x values over which to draw the normal distribution

x = np.linspace(df['log_amount'].min(), df['log_amount'].max(), 100)

# Calculate the mathematical function of the normal distribution

# for the sample mean and sample standard devation of the log-transformed data

y = stats.norm.pdf(x, mean_log_amount, std_log_amount)

# Add the normal distribution estimated by the data over the data histogram

fig.add_trace(go.Scatter(x=x, y=y, mode='lines', name='Normal Distribution',

line=dict(color='red')))

fig.update_layout(

title='Normal Distribution Estimation of Log Transformed Amount',

xaxis_title='Log Transformed Amount', yaxis_title='Probability Density',

showlegend=True)

fig.show()