Arch topics - PepperDash/Essentials GitHub Wiki

Configuration topics

Configuration is central to Essentials. On this page we will cover configuration-related topics, including the important concept of configure-first and some details about the config file process.

Classes Referenced

PepperDash.Essentials.Core.Config.DeviceConfig

Configure-first development

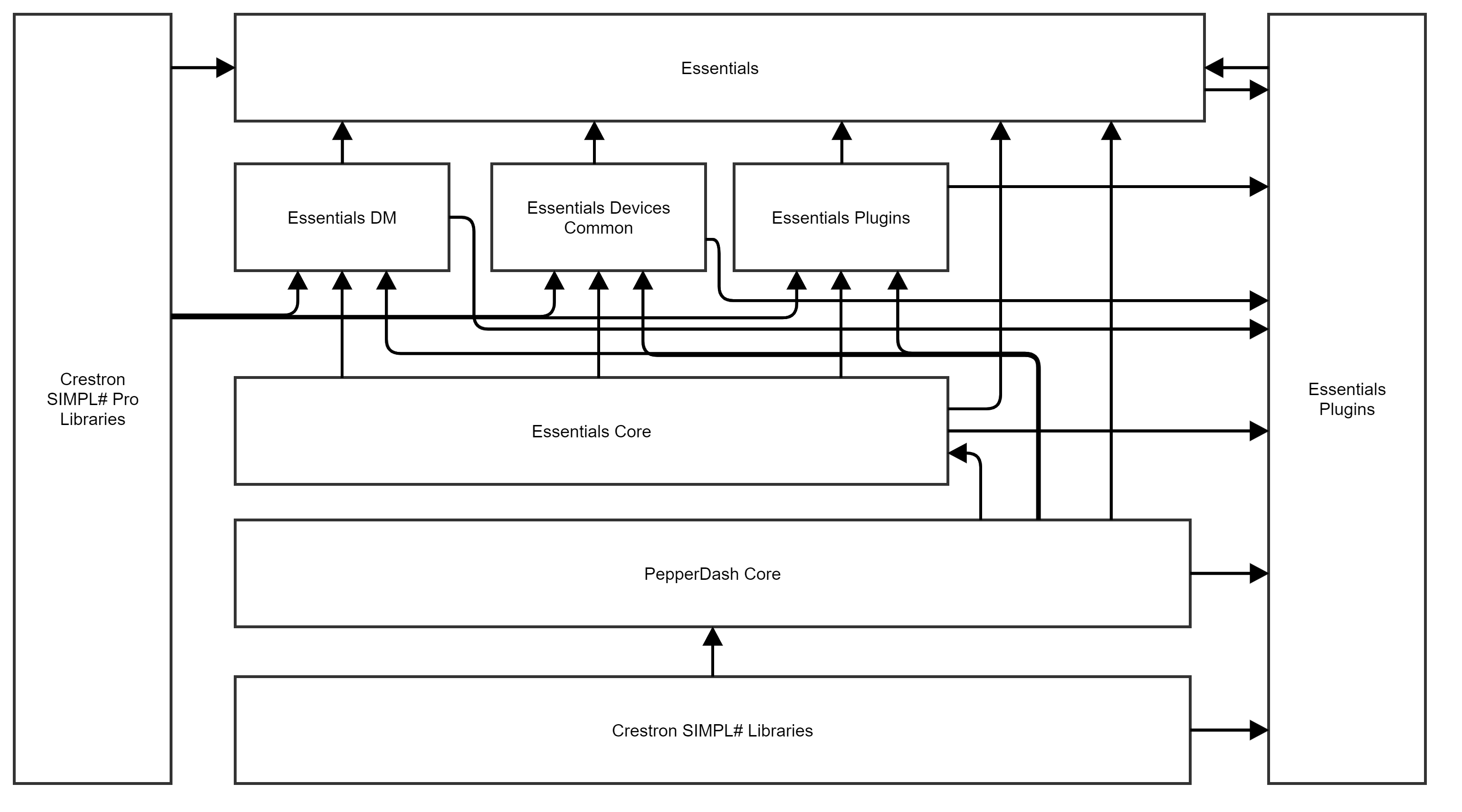

Framework Libraries

The table below is meant to serve as a guide to understand the basic organization of code concepts within the various libraries that make up the architecture.

Todo, try a text-based table:

The diagram below shows the reference dependencies that exist between the different component libraries that make up the Essentials Framework.

Architecture

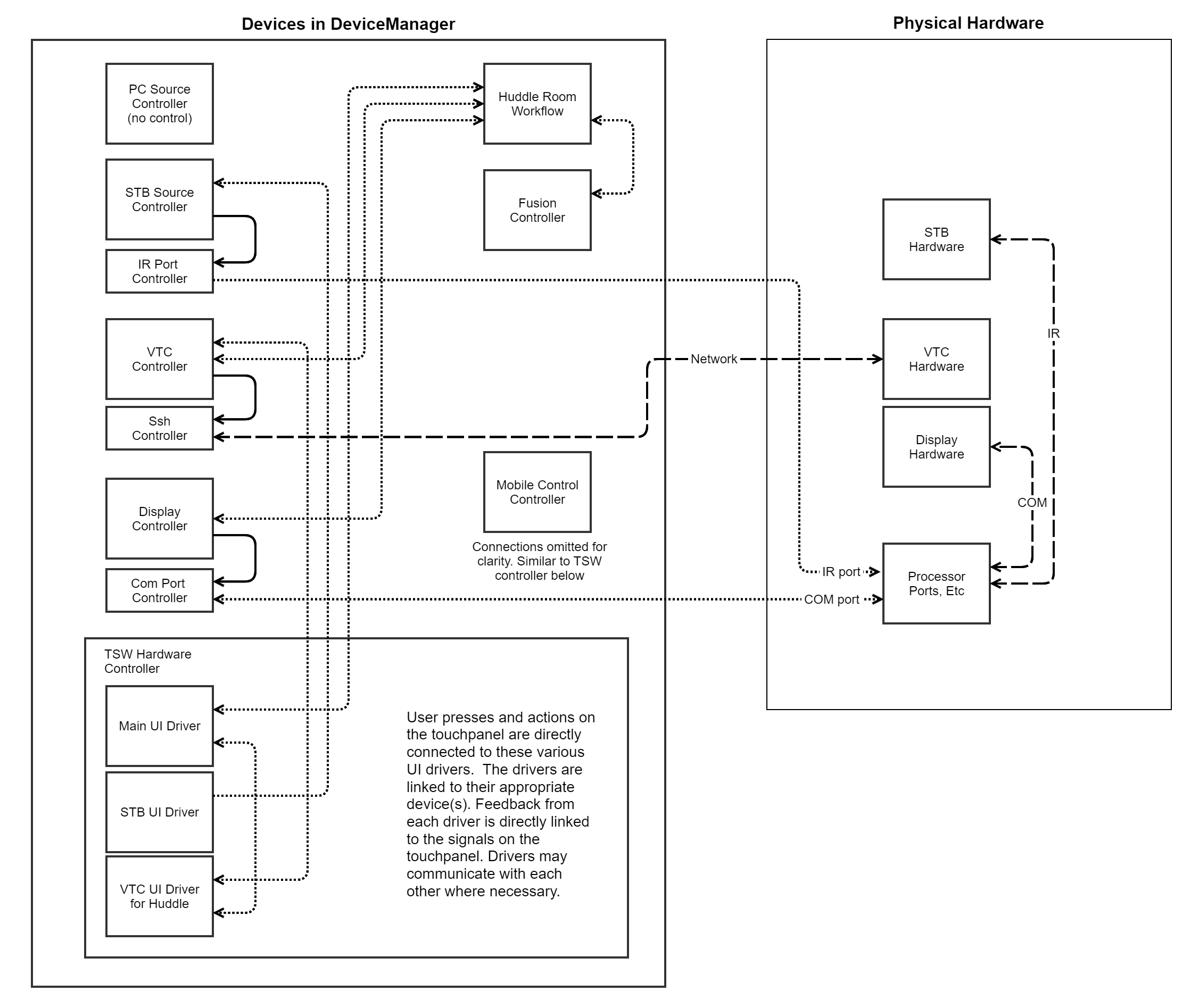

Device and DeviceManager

A Device is a logical construct. It may represent a piece of hardware, a port, a socket, a collection of other devices/ports/constructs that define an operation, or any unit of logic that should be created at startup and exist independent of other devices.

DeviceManager is the collection of all Devices. The collection of everything we control on a system. ADD SOME MORE HERE

Flat system design

In Essentials, most everything we do is focused in one layer: The Devices layer. This layer interacts with the physical Crestron and other hardware and logical constructs underneath, and is designed so that we rarely act directly on the often-inconsistent hardware layer. The DeviceManager is responsible for containing all of the devices in this layer.

Types of devices:

- Rooms

- Sources

- Codecs, DSPs, displays, routing hardware

- IR Ports, Com ports, SSh Clients, ...

- Occupancy sensors and relay-driven devices

- Logical devices that manage multiple devices and other business, like shade or lighting scene controllers

- Fusion connectors to rooms

A Device doesn't always represent a physical piece of hardware, but rather a logical construct that "does something" and is used by one or more other devices in the running program. For example, we create a room device, and its corresponding Fusion device, and that room has a Cisco codec device, with an attached SSh client device. All of these lie in a flat collection in the DeviceManager.

The

DeviceManageris nothing more than a modified collection of things, and technically those things don't have to be Devices, but must at least implement theIKeyedinterface (simply so items can be looked up by their key.) Items in theDeviceManagerthat are Devices are run through additional steps of activation at startup. This collection of devices is all interrelated by their string keys.

In this flat design, we spin up devices, and then introduce them to their "coworkers and bosses" - the other devices and logical units that they will interact with - and get them all operating together to form a running unit. For example: A room configuration will contain a "VideoCodecKey" property and a "DefaultDisplayKey" property. The DeviceManager provides the room with the codec or displays having the appropriate keys. What the room does with those is dependent on its coding.

In the default Essentials routing scheme, the routing system gets the various devices involved in given route from

DeviceManager, as they are discovered along the defined tie-lines. This is all done at route-time, on the fly, using only device and port keys. As soon as the routing operation is done, the whole process is released from memory. This is extremely-loose coupling between objects.

This flat structure ensures that every device in a system exists in one place and may be shared and reused with relative ease. There is no hierarchy.

Architecture drawing

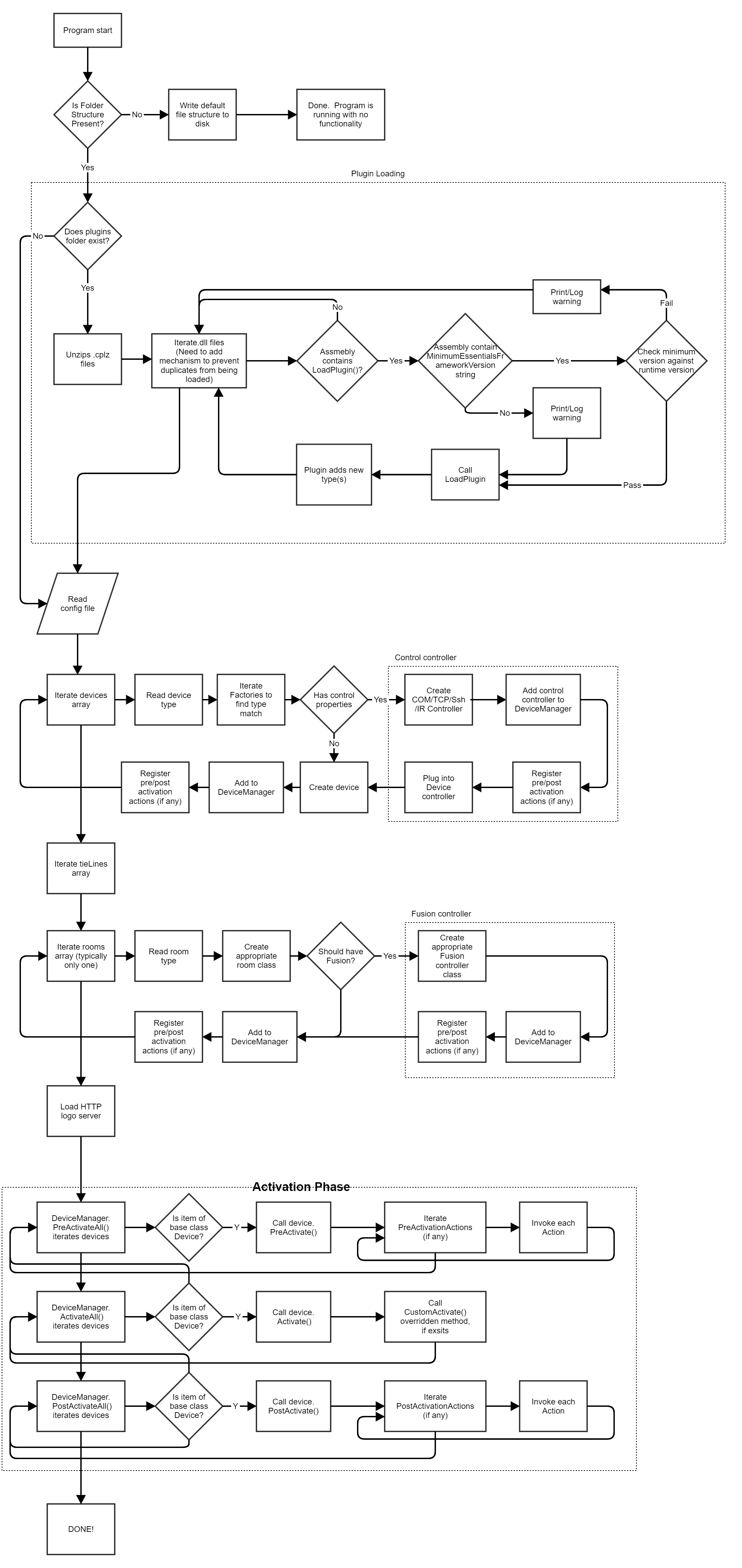

Essentials Configurable System Lifecycle

Activation phases additional topics and examples (OTHER DOCS)

Concepts (link)

Room and touchpanel activation (link)

Configure first development

One of the primary concepts that has been adopted and must be adhered to when writing for Essentials framework is the concept of "configure first." The simple version is: Write what you need to do in the related configuration file (and configuration tool) first, then write the code that runs from that configuration. This ensures that the running code can actually be configured in the "flat" structure of devices and rooms that Essentials uses.

Often, code is written and tested first without consideration for configurability. Then, when a developer tries to make it configurable, they discover that the code as written doesn’t support it without complicated configuration files. This creates spaghetti code in tools that are written to generate configurations and tends to create tighter coupling between objects than we desire. Later, a modified version of the original program is desired, but because the code was written in such a specific fashion, the code is hard to refactor and extend. This causes the configuration tool and configuration files to become even more convoluted. The modern versions of configuration tools that are starting to come out are modular and componentized. We want to ensure as much re-use of these modules as possible, with extensions and added features added on, rather than complete rewrites of existing code. In our running systems, we want to ensure as much flexibility in design as possible, eliminating multiple classes with similar code.

Configuration reader process

At the heart of the Essentials framework is the configuration system. While not technically necessary for a system written with the Essentials framework, it is the preferred and, currently, the only way to build an Essentials system. The configuration file is JSON, and well-defined (but not well documented, yet). It is comprised of blocks:

- info (object) Contains metadata about the config file

- devices (array) Contains, well, the devices we intend to build and load

- rooms (array, typically only one) Contains the rooms we need

- sourceLists (object) Used by one or more rooms to represent list(s) of sources for those rooms

- tieLines (array) Used by the routing system to discover routing between sources and displays

In addition, a downloaded Portal config file will most likely be in a template/system form, meaning that the file contains two main objects, representing the template configuration and its system-level overrides. Other metadata, such as Portal UUIDs or URLs may be present.

At startup, the configuration file is read, and a ReadyEvent is fired. Upon being ready, that configuration is loaded by the ConfigReader.LoadConfig() method. The template and system are merged into a single configuration object, and that object is then deserialized into configuration wrapper classes that define most of the structure of the program to be built. (Custom configuration objects were built to allow for better type handling rather than using JToken methods to parse out error-prone property names.)

For example, a DeviceConfig object:

namespace PepperDash.Essentials.Core.Config

{

public class DeviceConfig

{

[JsonProperty("key")]

public string Key { get; set; }

[JsonProperty("uid")]

public int Uid { get; set; }

[JsonProperty("name")]

public string Name { get; set; }

[JsonProperty("group")]

public string Group { get; set; }

[JsonProperty("type")]

public string Type { get; set; }

[JsonProperty("properties")]

[JsonConverter(typeof(DevicePropertiesConverter))]

public JToken Properties { get; set; }

}

}

Every Device present must adhere to those five properties plus a properties object. The properties object will have its own deserialization helpers, depending on what its structure is.

Once the ConfigReader has successfully read and deserialized the config file, then ControlSystem.Load() is called. This does the following in order:

- Loads Devices

- Loads TieLines

- Loads Rooms

- Loads LogoServer

- Activation sequence

This ordering ensures that all devices are at least present before building tie lines and rooms. Rooms can be built without their required devices being present. In principle, this could break from the loosely-coupled goal we have described, but it is the clearest way to build the system in code. The goal is still to build a room class that doesn't have functional dependencies on devices that may not be ready for use.

In each device/room step, a device factory process is called. We call subsequent device factory methods in the various libraries that make up Essentials until one of them returns a functional device. This allows us to break up the factory process into individual libraries, and not have a huge list of types and build procedures. Here's part of the code:

// Try local factories first

var newDev = DeviceFactory.GetDevice(devConf);

if (newDev == null)

newDev = BridgeFactory.GetDevice(devConf);

// Then associated library factories

if (newDev == null)

newDev = PepperDash.Essentials.Core.DeviceFactory.GetDevice(devConf);

if (newDev == null)

newDev = PepperDash.Essentials.Devices.Common.DeviceFactory.GetDevice(devConf);

if (newDev == null)

newDev = PepperDash.Essentials.DM.DeviceFactory.GetDevice(devConf);

if (newDev == null)

newDev = PepperDash.Essentials.Devices.Displays.DisplayDeviceFactory.GetDevice(devConf);

In each respective factory, or device constructor, the configuration's properties object is either converted to a config object or read from using JToken methods. This builds the device which may be ready to go, or may require activation as described above.

A similar process is carried out for rooms, but as of now, the room types are so few that they are all handled in the ControlSystem.LoadRooms() method.

This process will soon be enhanced by a plug-in mechanism that will drill into dynamically-loaded DLLs and load types from factories in those libraries. This is where custom essentials systems will grow from.

After those five steps, the system will be running and ready to use.