Python Getting Started and Basics - JohnHau/mis GitHub Wiki

I shall assume that you are familiar with some programming languages such as C/C++/Java. This article is NOT meant to be an introduction to programming.

I personally recommend that you learn a traditional general-purpose programming language (such as C/C++/Java) before learning scripting language like Python/JavaScript/Perl/PHP because they are less structure than the traditional languages with many fancy features.

- Python By Examples This section is for experienced programmers to look at Python's syntaxes and those who need to refresh their memory. For novices, go to the next section.

1.1 Syntax Summary and Comparison Comment: Python's comment begins with a '#' and lasts until the end-of-line. Python does not support multi-line comments. (C/C++/C#/Java end-of-line comment begins with '\'. They support multi-line comments via /* ... */.) String: Python's string can be delimited by either single quotes ('...') or double quotes ("..."). Python also supports multi-line string, delimited by either triple-single ('''...''') or triple-double quotes ("""..."""). Strings are immutable in Python. (C/C++/C#/Java use double quotes for string and single quotes for character. They do not support multi-line string.) Variable Type Declaration: Like most of the scripting interpreted languages (such as JavaScript/Perl), Python is dynamically typed. You do NOT need to declare variables (name and type) before using them. A variables is created via the initial assignment. Python associates types with the objects, not the variables, i.e., a variable can hold object of any types. (In C/C++/C#/Java, you need to declare the name and type of a variable before using it.) Data Types: Python support these data types: int (integers), float (floating-point numbers), str (String), bool (boolean of True or False), and more. Statements: Python's statement ends with a newline. (C/C++/C#/Java's statement ends with a semi-colon (;)) Compound Statements and Indentation: Python uses indentation to indicate body-block. (C/C++/C#/Java use braces {}.) header_1: # Headers are terminated by a colon statement_1_1 # Body blocks are indented (recommended to use 4 spaces) statement_1_2 ...... header_2: statement_2_1 statement_2_2 ......

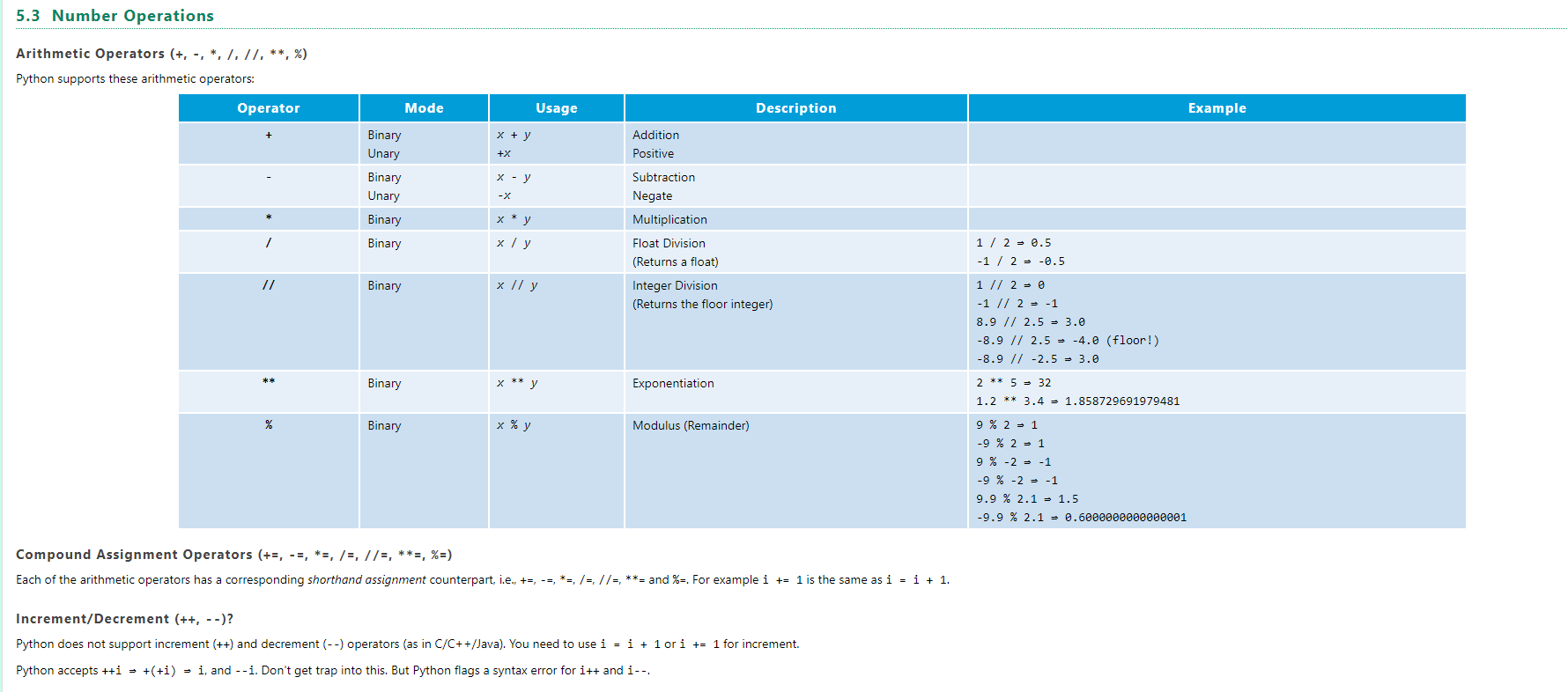

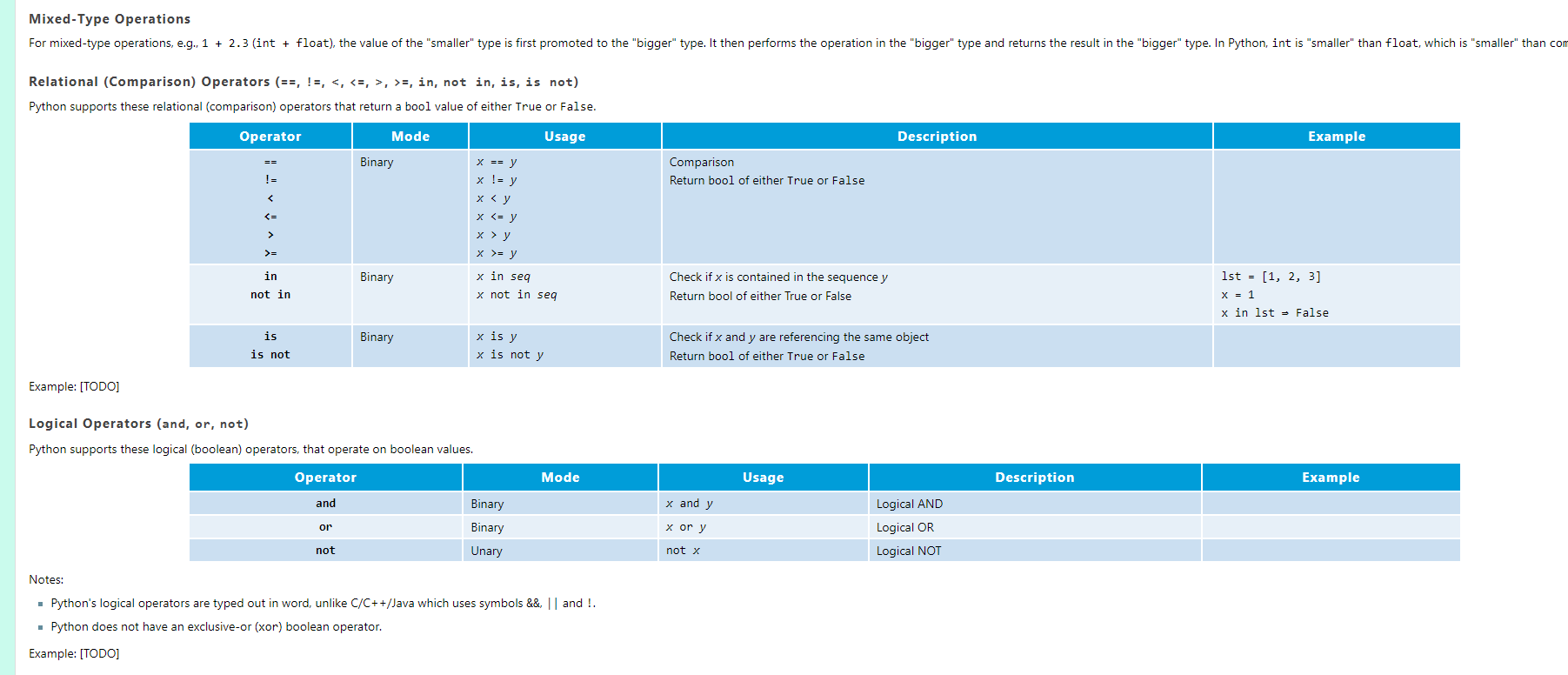

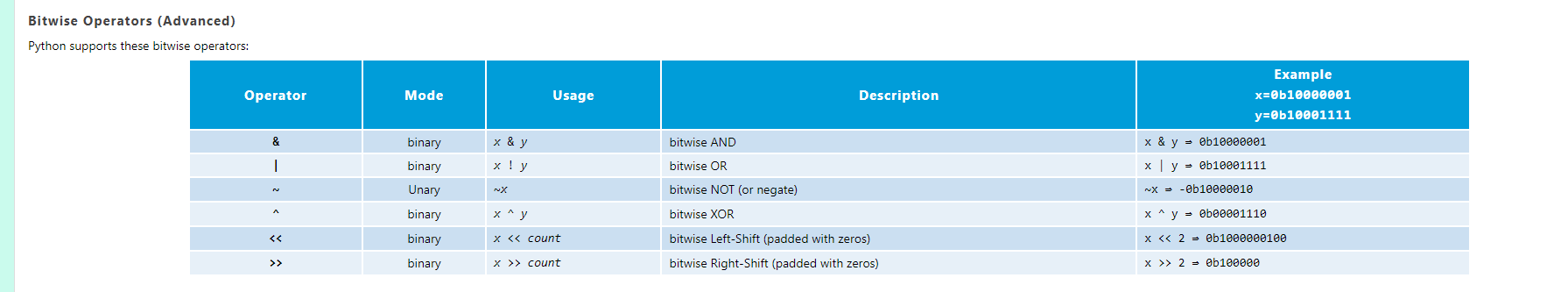

header_1: statement_1_1; statement_1_2; ...... header_2: statement_2_1; statement_2_2; ...... This syntax forces you to indent the program correctly which is crucial for reading your program. You can use space or tab for indentation (but not mixture of both). Each body level must be indented at the same distance. It is recommended to use 4 spaces for each level of indentation. Assignment Operator: = Arithmetic Operators: + (add), - (subtract), * (multiply), / (divide), // (integer divide), ** (exponent), % (modulus). (++ and -- are not supported) Compound Assignment Operators: +=, -=, *=, /=, //=, **=, %=. Comparison Operators: ==, !=, <, <=, >, >=, in, not in, is, not is. Logical Operators: and, or, not. (C/C++/C#/Java use &&, || and !) Conditional:

if test: # no parentheses needed for test true_block else: # Optional false_block

if test_1: block_1 elif test_2: block_2 ...... elif test_n: block_n else: else_block

true_expr if test else false_expr Loop:

while test: # no parentheses needed for test true_block else: # Optional, run only if no break encountered else_block

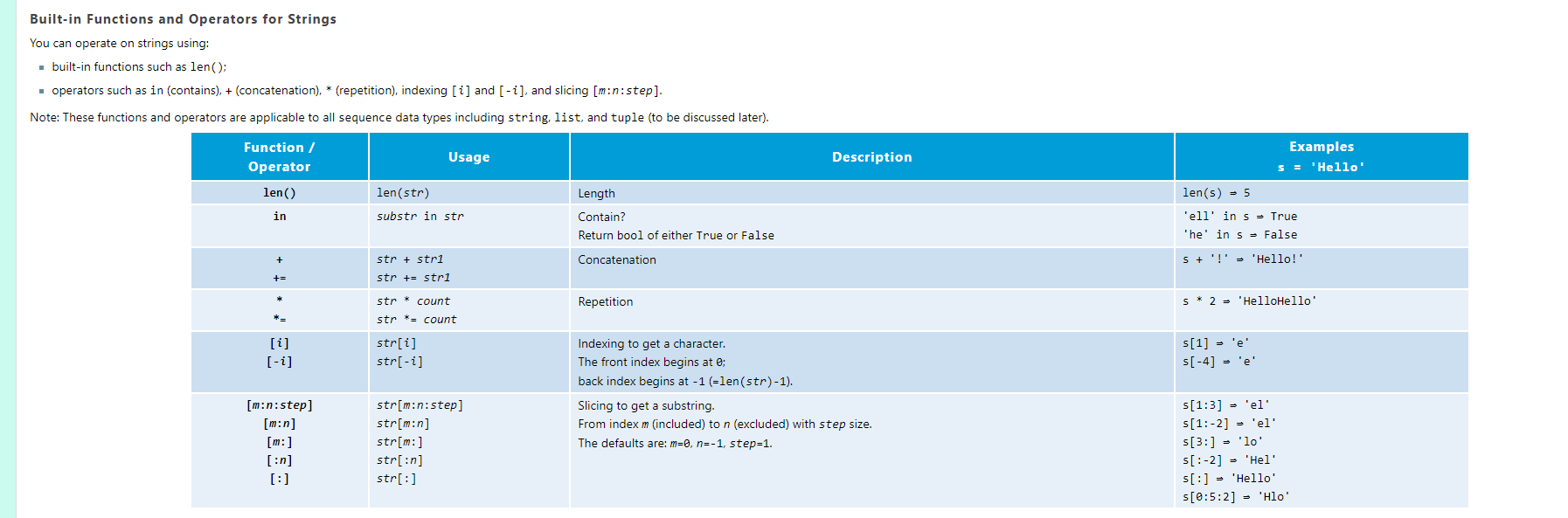

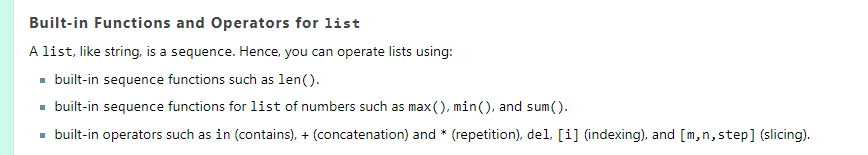

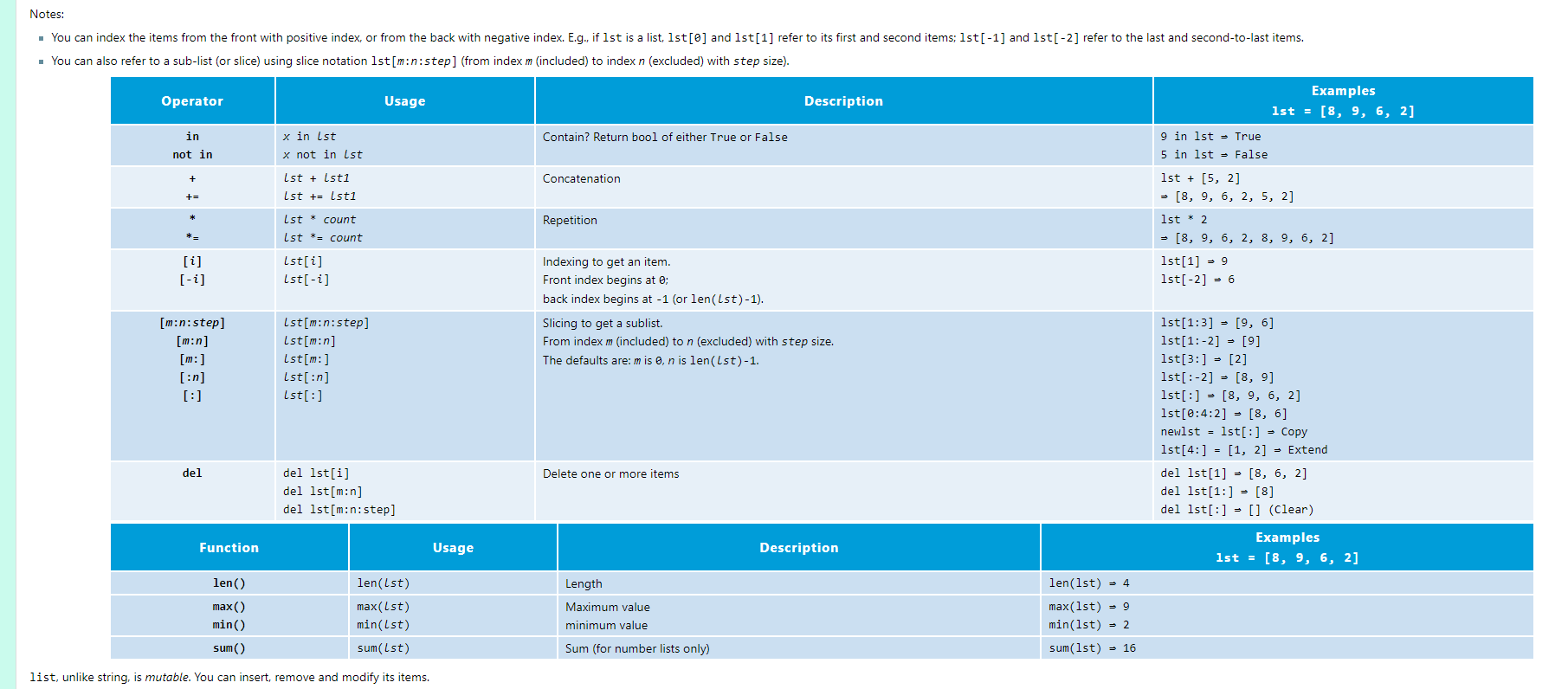

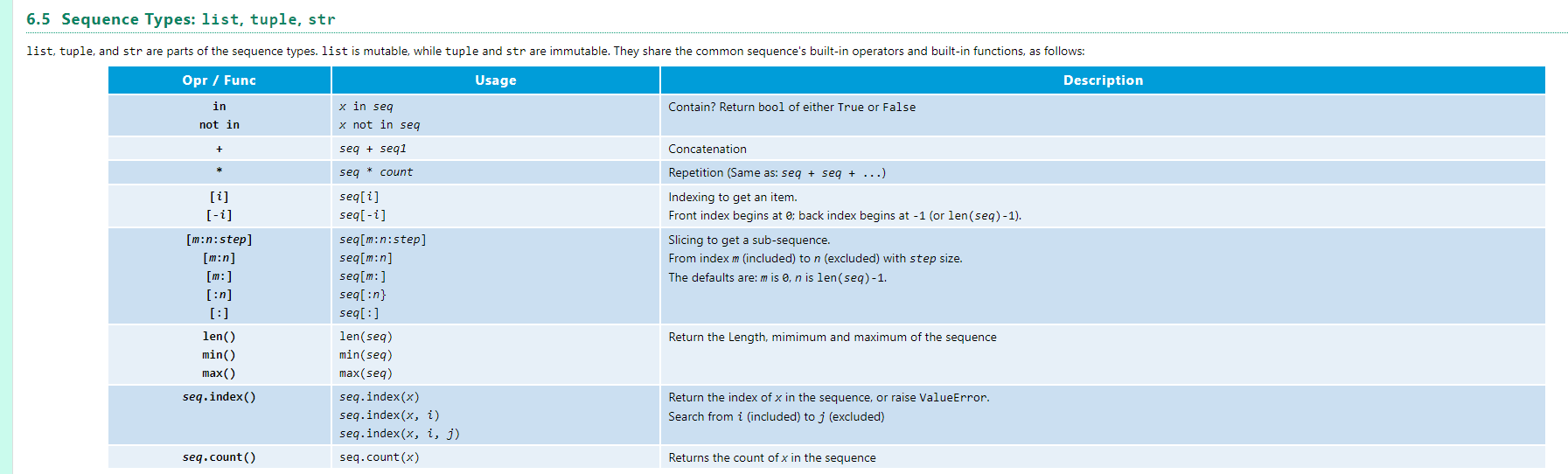

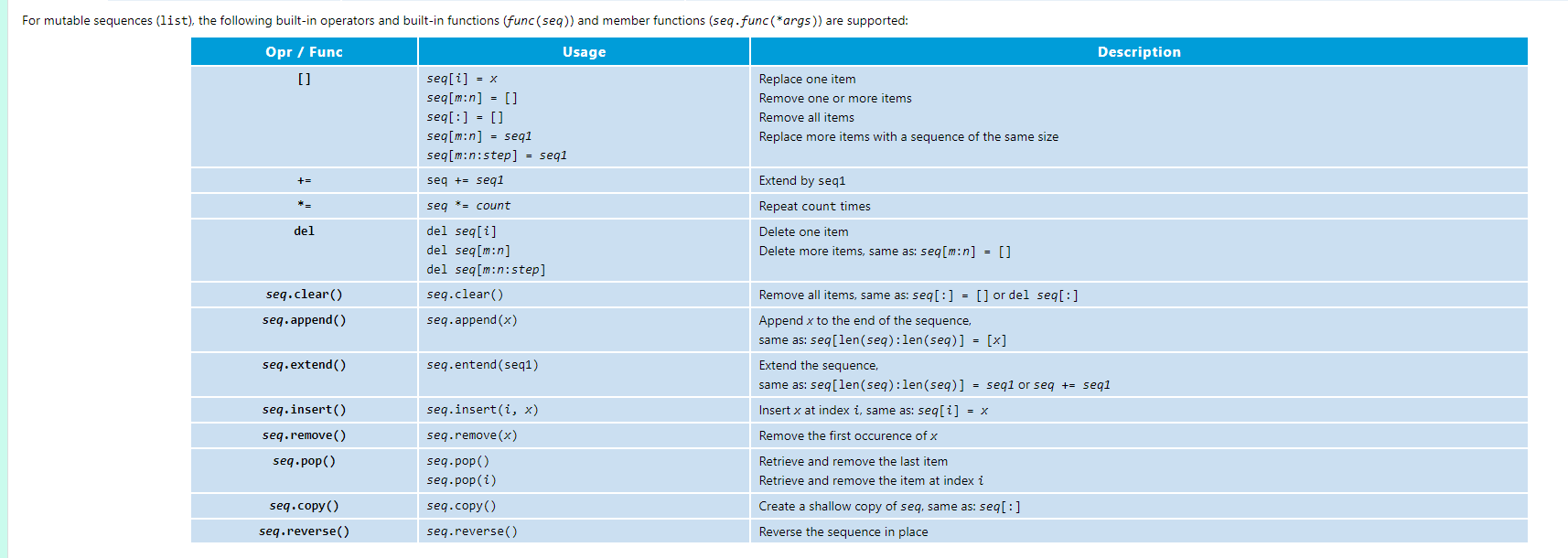

for item in sequence: true_block else: # Optional, run only if no break encountered else_block Python does NOT support the traditional C-like for-loop with index: for (int i, i < n, ++i). List: Python supports variable-size dynamic array via a built-in data structure called list, denoted as lst=[v1, v2, ..., vn]. List is similar to C/C++/C#/Java's array but NOT fixed-size. You can refer to an element via lst[i] or lst[-i], or sub-list via lst[m:n:step]. You can use built-in functions such as len(lst), sum(lst), min(lst). Data Structures: List: [v1, v2, ...] (mutable dynamic array). Tuple: (v1, v2, v3, ...) (Immutable fix-sized array). Dictionary: {k1:v1, k2:v2, ...} (mutable key-value pairs, associative array, map). Set: {k1, k2, ...} (with unique key and mutable). Sequence (String, Tuple, List) Operators and Functions: in, not in: membership test. +: concatenation *: repetition [i], [-i]: indexing [m:n:step]: slicing len(seq), min(seq), max(seq) seq.index(), seq.count() For mutable sequences (list) only: Assignment via [i], [-i] (indexing) and [m:n:step] (slicing) Assignment via =, += (compound concatenation), *= (compound repetition) del: delete seq.clear(), seq.append(), seq.extend(), seq.insert(), seq.remove(), seq.pop(), seq.copy(), seq.reverse() Function Definition: def functionName(*args, **kwargs): # Positional and keyword arguments body return return_vale 1.2 Example grade_statistics.py - Basic Syntaxes and Constructs This example repeatably prompts user for grade (between 0 and 100 with input validation). It then compute the sum, average, minimum, and print the horizontal histogram.

This example illustrates the basic Python syntaxes and constructs, such as comment, statement, block indentation, conditional if-else, for-loop, while-loop, input/output, string, list and function.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 #!/usr/bin/env python3

""" grade_statistics - Grade statistics

Prompt user for grades (0-100 with input validation) and compute the sum, average,

minimum, and print the horizontal histogram.

An example to illustrate basic Python syntaxes and constructs, such as block indentation,

conditional, for-loop, while-loop, input/output, list and function.

Usage: ./grade_statistics.py (Unix/Mac OS)

python3 grade_statistics.py (All Platforms)

"""

# Define all the functions before using them

def my_sum(lst):

"""Return the sum of the given list."""

sum = 0

for item in lst: sum += item

return sum

def my_average(lst):

"""Return the average of the given list."""

return my_sum(lst)/len(lst) # float

def my_min(lst):

"""Return the minimum of the given lst."""

min = lst[0]

for item in lst:

if item < min: # Parentheses () not needed for test

min = item

return min

def print_histogram(lst):

"""Print the horizontal histogram."""

# Create a list of 10 bins to hold grades of 0-9, 10-19, ..., 90-100.

# bins[0] to bins[8] has 10 items, but bins[9] has 11 items.

bins = [0]*10 # Use repetition operator (*) to create a list of 10 zeros

# Populate the histogram bins from the grades in the given lst.

for grade in lst:

if grade == 100: # Special case

bins[9] += 1

else:

bins[grade//10] += 1 # Use // for integer divide to get a truncated int

# Print histogram

# 2D pattern: rows are bins, columns are value of that particular bin in stars

for row in range(len(bins)): # [0, 1, 2, ..., len(bins)-1]

# Print row header

if row == 9: # Special case

print('{:3d}-{:<3d}: '.format(90, 100), end='') # Formatted output (new style), no newline

else:

print('{:3d}-{:<3d}: '.format(row*10, row*10+9), end='') # Formatted output, no newline

# Print one star per count

for col in range(bins[row]): print('*', end='') # no newline

print() # newline

# Alternatively, use str's repetition operator (*) to create the output string

#print('*'*bins[row])

def main():

"""The main function."""

# Create an initial empty list for grades to receive from input

grade_list = []

# Read grades with input validation

grade = int(input('Enter a grade between 0 and 100 (or -1 to end): '))

while grade != -1:

if 0 <= grade <= 100: # Python support this comparison syntax

grade_list.append(grade)

else:

print('invalid grade, try again...')

grade = int(input('Enter a grade between 0 and 100 (or -1 to end): '))

# Call functions and print results

print('---------------')

print('The list is:', grade_list)

print('The minimum is:', my_min(grade_list))

print('The minimum using built-in function is:', min(grade_list)) # Using built-in function min()

print('The sum is:', my_sum(grade_list))

print('The sum using built-in function is:', sum(grade_list)) # Using built-in function sum()

print('The average is: %.2f' % my_average(grade_list)) # Formatted output (old style)

print('The average is: {:.2f}'.format(my_average(grade_list))) # Formatted output (new style)

print('---------------')

print_histogram(grade_list)

# Run the main() function

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

To run the Python script:

# (All platforms) Invoke Python Interpreter to run the script

$ cd /path/to/project_directory

$ python3 grade_statistics.py

# (Unix/Mac OS/Cygwin) Set the script to executable, and execute the script

$ cd /path/to/project_directory

$ chmod u+x grade_statistics.py

$ ./grade_statistics.py

The expected output is:

$ Python3 grade_statistics.py

Enter a grade between 0 and 100 (or -1 to end): 9

Enter a grade between 0 and 100 (or -1 to end): 999

invalid grade, try again...

Enter a grade between 0 and 100 (or -1 to end): 101

invalid grade, try again...

Enter a grade between 0 and 100 (or -1 to end): 8

Enter a grade between 0 and 100 (or -1 to end): 7

Enter a grade between 0 and 100 (or -1 to end): 45

Enter a grade between 0 and 100 (or -1 to end): 90

Enter a grade between 0 and 100 (or -1 to end): 100

Enter a grade between 0 and 100 (or -1 to end): 98

Enter a grade between 0 and 100 (or -1 to end): -1

---------------

The list is: [9, 8, 7, 45, 90, 100, 98]

The minimum is: 7

The minimum using built-in function is: 7

The sum is: 357

The sum using built-in function is: 357

The average is: 51.00

---------------

0-9 : ***

10-19 :

20-29 :

30-39 :

40-49 : *

50-59 :

60-69 :

70-79 :

80-89 :

90-100: ***

How it Works

#!/usr/bin/env python3 (Line 1) is applicable to the Unix environment only. It is known as the Hash-Bang (or She-Bang) for specifying the location of Python Interpreter, so that the script can be executed directly as a standalone program.

# -*- coding: UTF-8 -*- (Line 2, optional) specifies the source encoding scheme for saving the source file. We choose and recommend UTF-8 for internationalization. This special format is recognized by many popular editors for saving the source code in the specified encoding format.

Doc-String: The script begins by the so-called doc-string (documentation string )(Line 3-12) to provide the documentation for this Python module. Doc-string is a multi-line string (delimited by triple-single or triple-double quoted), which can be extracted from the source file to create documentation.

def my_sum(lst): (Line 15-20): We define a function called my_sum() which takes a list and return the sum of the items. It uses a for-each-in loop to iterate through all the items of the given list. As Python is interpretative, you need to define the function first, before using it. We choose the function name my_sum(list) to differentiate from the built-in function sum(list).

bins = [0]*10 (Line 38): Python supports repetition operator (*). This statement creates a list of ten zeros. Similarly, repetition operator (*) can be apply on string (Line 59).

for row in range(len(bins)): (Line 48, 56): Python supports only for-in loop. It does NOT support the traditional C-like for-loop with index. Hence, we need to use the built-in range(n) function to create a list of indexes [0, 1, ..., n-1], then apply the for-in loop on the index list.

0 <= grade <= 100 (Line 68): Python supports this syntax for comparison.

There are a few ways of printing:

print() built-in function (Line 75-80):

print(*objects, sep=' ', end='\n', file=sys.stdout, flush=False)

# Print objects to the text stream file (default standard output sys.stdout),

# separated by sep (default space) and followed by end (default newline).

# *objects denotes variable number of positional arguments packed into a tuple.

By default, print() prints a newline at the end. You need to include argument end='' to suppress the newline.

print(str.format()) (Line 51, 53): Python 3's new style for formatted string via str class member function str.format(). The string on which this method is called can contain literal text or replacement fields delimited by braces {}. Each replacement field contains either the numeric index of a positional argument, or the name of a keyword argument, with C-like format specifiers beginning with : (instead of % in C) such as :4d for integer, :6.2f for floating-point number, and :-5s for string, and flags such as < for left-align, > for right-align, ^ for center-align.

print('formatting-string' % args) (Line 81): Python 2's old style for formatted string using % operator. The formatting-string could contain C-like format-specifiers, such as %4d for integer, %6.2f for floating-point number, %8s for string. This line is included in case you need to read old programs. I suggest you do use the new Python 3's formatting style.

grade = int(input('Enter ... ')) (Line 66, 72): You can read input from standard input device (default to keyboard) via the built-in input() function.

input([prompt])

# The optional prompt argument is written to standard output without a trailing newline.

# The function then reads a line from input, converts it to a string (stripping a trailing newline),

# and returns the string.

As the input() function returns a string, we need to cast it to int.

if __name__ == '__main__': (Line 87): When you execute a Python module via the Python Interpreter, the global variable __name__ is set to '__main__'. On the other hand, when a module is imported into another module, its __name__ is set to the module name. Hence, the above module will be executed if it is loaded by the Python interpreter, but not imported by another module. This is a good practice for testing a module.

1.3 Example number_guess.py - Guess a Number

This is a number guessing game. It illustrates nested-if (if-elif-else), while-loop with bool flag, and random module. For example,

Enter your guess (between 0 and 100): 50

Try lower...

Enter your guess (between 0 and 100): 25

Try higher...

Enter your guess (between 0 and 100): 37

Try higher...

Enter your guess (between 0 and 100): 44

Try lower...

Enter your guess (between 0 and 100): 40

Try lower...

Enter your guess (between 0 and 100): 38

Try higher...

Enter your guess (between 0 and 100): 39

Congratulation!

You got it in 7 trials.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# -*- coding: UTF-8 -*-

"""

number_guess - Number guessing game

Guess a number between 0 and 100. This example illustrates while-loop with boolean flag, nested-if, and random module.

Usage: number_guess.py """ import random # Using random.randint()

secret_number = random.randint(0, 100) # return a random int between [0, 100] trial_number = 0 # number of trials done = False # bool flag for loop control

while not(done): trial_number += 1 number_in = (int)(input('Enter your guess (between 0 and 100): ')) if number_in == secret_number: print('Congratulation!') print('You got it in {} trials.'.format(trial_number)) # Formatted printing done = True elif number_in < secret_number: print('Try higher...') else: print('Try lower...') How it Works import random (Line 12): We are going to use random module's randint() function to generate a secret number. In Python, you need to import the module (external library) before using it. random.randint(0, 100) (Line 15): Generate a random integer between 0 and 100 (both inclusive). done = False (Line 17): Python supports a bool type for boolean values of True or False. We use this boolean flag to control our while-loop. The syntax for while-loop (Line 19) is: while boolean_test: # No need for () around the test loop_body The syntax for nested-if (Line 22) is: if boolean_test_1: # No need for () around the test block_1 elif boolean_test_2: block_2 ...... else: else_block 1.4 Exmaple magic_number.py - Check if Number Contains a Magic Digit This example prompts user for a number, and check if the number contains a magic digit. This example illustrate function, int and str operations. For example,

Enter a number: 123456789 123456789 is a magic number 123456789 is a magic number 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 #!/usr/bin/env python3

""" magic_number - Check if the given number contains a magic digit

Prompt user for a number, and check if the number contains a magic digit.

Usage: magic_number.py

"""

def isMagic(number:int, magicDigit:int = 8) -> bool:

"""Check if the given number contains the digit magicDigit.

Arguments:

number - positive int only

magicDigit - single-digit int (default is 8)

"""

while number > 0:

# extract and drop each digit

if number % 10 == magicDigit:

return True # break loop

else:

number //= 10 # integer division

return False

def isMagicStr(numberStr:str, magicDigit:str = '8') -> bool:

"""Check if the given number string contains the magicDigit

Arguments:

numberStr - a numeric str

magicDigit - a single-digit str (default is '8')

"""

return magicDigit in numberStr # Use built-in sequence operator 'in'

def main():

"""The main function"""

# Prompt and read input string as int

numberIn = int(input('Enter a number: '))

# Use isMagic()

if isMagic(numberIn):

print('{} is a magic number'.format(numberIn))

else:

print('{} is NOT a magic number'.format(numberIn))

# Use isMagicStr()

if isMagicStr(str(numberIn), '9'):

print('{} is a magic number'.format(numberIn))

else:

print('{} is NOT a magic number'.format(numberIn))

# Run the main function

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

How it Works

We organize the program into functions.

We implement two versions of function to check for magic number - an int version (Line 10) and a str version (Line 25) - for academic purpose.

def isMagic(number:int, magicDigit:int = 8) -> bool: (Line 10): The hightlight parts are known as type hint annotations. They are ignored by Python Interpreter, and merely serves as documentation.

if __name__ == '__main__': (Line 51): When you execute a Python module via the Python Interpreter, the global variable __name__ is set to '__main__'. On the other hand, when a module is imported into another module, its __name__ is set to the module name. Hence, the above module will be executed if it is loaded by the Python interpreter, but not imported by another module. This is a good practice for testing a module.

1.5 Example hex2dec.py - Hexadecimal To Decimal Conversion

This example prompts user for a hexadecimal (hex) string, and print its decimal equivalent. It illustrates for-loop with index, nested-if, string operation and dictionary (associative array). For example,

Enter a hex string: 1abcd

The decimal equivalent for hex "1abcd" is: 109517

The decimal equivalent for hex "1abcd" using built-in function is: 109517

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# -*- coding: UTF-8 -*-

"""

hex2dec - hexadecimal to decimal conversion

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Prompt user for a hex string, and print its decimal equivalent

This example illustrates for-loop with index, nested-if, string operations and dictionary.

Usage: hex2dec.py

"""

import sys # Using sys.exit()

dec = 0 # Accumulating from each hex digit

dictHex2Dec = {'a': 10, 'b': 11, 'c': 12, 'd': 13, 'e': 14, 'f': 15} # lookup table for hex to dec

# Prompt and read hex string

hexStr = input('Enter a hex string: ')

# Process each hex digit from the left (most significant digit)

for hexDigitIdx in range(len(hexStr)): # hexDigitIdx = 0, 1, 2, ..., len()-1

hexDigit = hexStr[hexDigitIdx] # Extract each 1-character string

hexExpFactor = 16 ** (len(hexStr) - 1 - hexDigitIdx) # ** for power or exponent

if '1' <= hexDigit <= '9': # Python supports chain comparison

dec += int(hexDigit) * hexExpFactor

elif hexDigit == '0':

pass # Need a dummy statement for do nothing

elif 'A' <= hexDigit <= 'F':

dec += (ord(hexDigit) - ord('A') + 10) * hexExpFactor # ord() returns the Unicode number

elif 'a' <= hexDigit <= 'f':

dec += dictHex2Dec[hexDigit] * hexExpFactor # Look up from dictionary

else:

print('error: invalid hex string')

sys.exit(1) # Return a non-zero value to indicate abnormal termination

print('The decimal equivalent for hex "{}" is: {}'.format(hexStr, dec)) # Formatted output

# Using built-in function int(str, radix)

print('The decimal equivalent for hex "{}" using built-in function is: {}'.format(hexStr, int(hexStr, 16)))

How it Works

The conversion formula is: hn-1hn-2...h2h1h0 = hn-1×16n-1 + hn-2×16n-2 + ... + h2×162 + h1×161 + h0×160, where hi ∈ {0-9, A-F, a-f}.

import sys (Line 12): We are going to use sys module's exit() function to terminate the program for invalid input. In Python, we need to import the module (external library) before using it.

for hexDigitIdx in range(len(hexStr)): (Line 21): Python does not support the traditional C-like for-loop with index. It supports only for item in lst loop to iterate through each item in the lst. We use the built-in function range(n) to generate a list [0, 1, 2, ..., n-1], and then iterate through each item in the generated list.

In Python, we can iterate through each character of a string via the for-in loop, e.g.,

str = 'hello'

for ch in str: # Iterate through each character of the str

print(ch)

For this example, we cannot use the above as we need the index of the character to perform conversion.

hexDigit = hexStr[hexDigitIdx] (Line 22): In Python, you can use indexing operator str[i] to extract the i-th character. Take note that Python does not support character, but treat character as a 1-character string.

hexExpFactor = 16 ** (len(hexStr) - 1 - hexDigitIdx) (Line 23): Python supports exponent (or power) operator in the form of **. Take note that string index begins from 0, and increases from left-to-right. On the other hand, the hex digit's exponent begins from 0, but increases from right-to-left.

There are 23 cases of 1-character strings for hexDigit, '0'-'9', 'A'-'F', 'a'-'z', and other, which can be handled by 5 cases of nested-if as follows:

'1'-'9' (Line 24): we convert the string '1'-'9' to int 1-9 via int() built-in function.

'0' (Line 26): no nothing. In Python, you need to include a dummy statement called pass (Line 28) in the body block.

'A'-'F' (Line 28): To convert 1-character string 'A'-'F' to int 10-15, we use the ord(ch) built-in function to get the Unicode int of ch, subtract by the base 'A' and add 10.

'a'-'f' (Line 30): Python supports a data structure called dictionary (associative array), which contains key-value pairs. We created a dictionary dictHex2Dec (Line 15) to map 'a' to 10, 'b' to 11, and so on. We can then reference the dictionary via dic[key] to retrieve its value (Line 31).

other (Line 32): we use sys.exit(1) to terminate the program. We return a non-zero code to indicate abnormal termination.

1.6 Example bin2dec.py - Binary to Decimal Conversion

This example prompts user for a binary string (with input validation), and print its decimal equivalent. For example,

Enter a binary string: 1011001110

The decimal equivalent for binary "1011001110" is: 718

The decimal equivalent for binary "1011001110" using built-in function is: 718

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# -*- coding: UTF-8 -*-

"""

bin2dec - binary to decimal conversion

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Prompt user for a binary string, and print its decimal equivalent

Usage: bin2dec.py

"""

def validate(binStr:str) -> bool:

"""Check if the given str is a binary string (containing '0' and '1' only)"""

for ch in binStr:

if not(ch == '0' or ch == '1'): return False

return True

def convert(binStr:str) -> int:

"""Convert the binary string into its equivalent decimal"""

dec = 0 # Accumulate from each bit

# Process each bit from the left (most significant digit)

for bitIdx in range(len(binStr)): # bitIdx = 0, 1, 2, ..., len()-1

bit = binStr[bitIdx]

if bit == '1':

dec += 2 ** (len(binStr) - 1 - bitIdx) # ** for power

return dec

def main():

"""The main function"""

# Prompt and read binary string

binStr = input('Enter a binary string: ')

if not validate(binStr):

print('error: invalid binary string "{}"'.format(binStr))

else:

print('The decimal equivalent for binary "{}" is: {}'.format(binStr, convert(binStr)))

# Using built-in function int(str, radix)

print('The decimal equivalent for binary "{}" using built-in function is: {}'.format(binStr, int(binStr, 2)))

# Run the main function

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

How it Works

We organize the code in functions.

The conversion formula is: bn-1bn-2...b2b1b0 = bn-1×2n-1 + bn-2×2n-2 + ... + b2×22 + b1×21 + b0×20, where bi ∈ {0, 1}

You can use built-in function int(str, radix) to convert a number string from the given radix to decimal (Line 38).

1.7 Example dec2hex.py - Decimal to Hexadecimal Conversion

This program prompts user for a decimal number, and print its hexadecimal equivalent. For example,

Enter a decimal number: 45678

The hex for decimal 45678 is: B26E

The hex for decimal 45678 using built-in function is: 0xb26e

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# -*- coding: UTF-8 -*-

"""

dec2hex - decimal hexadecimal to conversion

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Prompt user for a decimal number, and print its hexadecimal equivalent

Usage: dec2hex.py

"""

hexStr = '' # To be accumulated

hexChars = [ # Use this list as lookup table for converting 0-15 to 0-9A-F

'0','1','2','3', '4','5','6','7', '8','9','A','B', 'C','D','E','F'];

# Prompt and read decimal number

dec = int(input('Enter a decimal number: ')) # positive int only

decSave = dec # We will destroy dec

# Repeated modulus/division and get the hex digits in reverse order

while dec > 0:

hexDigit = dec % 16; # 0-15

hexStr = hexChars[hexDigit] + hexStr; # Append in front corresponds to reverse order

dec = dec // 16; # Integer division

print('The hex for decimal {} is: {}'.format(decSave, hexStr)) # Formatted output

# Using built-in function hex(decNumber)

print('The hex for decimal {} using built-in function is: {}'.format(decSave, hex(decSave)))

How it Works

We use the modulus/division repeatedly to get the hex digits in reverse order.

We use a look-up list (Line 11) to convert int 0-15 to hex digit 0-9A-F.

You can use built-in function hex(decNumber), oct(decNumber), bin(decNunber) to convert decimal to hexadecimal, octal and binary, respectively; or use the more general format() function. E.g.,

>>> format(1234, 'x') # lowercase a-f

'4d2'

>>> format(1234, 'X') # uppercase A-F

'4D2'

>>> format(1234, 'o')

'2322'

>>> format(1234, 'b')

'10011010010'

>>> format(0x4d2, 'b')

'10011010010'

>>> hex(1234)

'0x4d2'

>>> oct(1234)

'0o2322'

>>> bin(1234)

'0b10011010010'

# Print a string in ASCII code

>>> str = 'hello'

>>> ' '.join(format(ord(ch), 'x') for ch in str)

'68 65 6c 6c 6f'

1.8 Example wc.py - Word Count

This example reads a filename from command-line and prints the line, word and character counts (similar to wc utility in Unix). It illustrates the text file input and text string processing.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# -*- coding: UTF-8 -*-

"""

wc - word count

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Read a file given in the command-line argument and print the number of

lines, words and characters - similar to UNIX's wc utility.

Usage: wc.py filename

"""

# Check if a filename is given in the command-line arguments using "sys" module

import sys # Using sys.argv and sys.exit()

if len(sys.argv) != 2: # Command-line arguments are kept in a list sys.argv

print('Usage: ./wc.py filename')

sys.exit(1) # Return a non-zero value to indicate abnormal termination

# You do not need to declare the name and type of variables.

# Variables are created via the initial assignments.

num_words = num_lines = num_chars = 0 # chain assignment

# Get input file name from list sys.argv

# sys.argv[0] is the script name, sys.argv[1] is the filename.

with open(sys.argv[1]) as infile: # 'with-as' closes the file automatically

for line in infile: # Process each line (including newline) in a for-loop

num_lines += 1 # No ++ operator in Python?!

num_chars += len(line)

line = line.strip() # Remove leading and trailing whitespaces

words = line.split() # Split into a list using whitespace as delimiter

num_words += len(words)

# Various ways of printing results

print('Number of Lines is', num_lines) # Items separated by blank

print('Number of Words is: {0:5d}'.format(num_words)) # new formatting style

print('Number of Characters is: %8.2f' % num_chars) # old formatting style

# Invoke Unix utility 'wc' through shell command for comparison

from subprocess import call # Python 3

call(['wc', sys.argv[1]]) # Command in a list

import os # Python 2

os.system('wc ' + sys.argv[1]) # Command is a str

How it works

import sys (Line 14): We use the sys module (@ https://docs.python.org/3/library/sys.html) from the Python's standard library to retrieve the command-line arguments kept in list sys.argv, and to terminate the program via sys.exit(). In Python, you need to import the module before using it.

The command-line arguments are stored in a variable sys.argv, which is a list (Python's dynamic array). The first item of the list sys.argv[0] is the script name, followed by the other command-line arguments.

if len(sys.argv) != 2: (Line 15): We use the built-in function len(list) to verify that the length of the command-line-argument list is 2.

with open(sys.argv[1]) as infile: (Line 25): We open the file via a with-as statement, which closes the file automatically upon exit.

for line in infile: (Line 26): We use a foreach-in loop (Line 29) to process each line of the infile, where line belong to the built-in class "str" (meant for string support @ https://docs.python.org/3/library/stdtypes.html#str). We use the str class' member functions strip() to strip the leading and trailing white spaces; and split() to split the string into a list of words.

str.strip([chars])

# Return a copy of the string with leading and trailing characters removed.

# The optional argument chars is a string specifying the characters to be removed.

# Default is whitespaces '\t\n '.

str.split(sep=None, maxsplit=-1)

# Return a list of the words in the string, using sep as the delimiter string.

# If maxsplit is given, at most maxsplit splits are done (thus, the list will have at most maxsplit+1 elements).

We also invoke the Unix utility "wc" via external shell command in 2 ways: via subprocess.call() and os.system().

1.9 Example htmlescape.py - Escape Reserved HTML Characters

This example reads the input and output filenames from the command-line and replaces the reserved HTML characters by their corresponding HTML entities. It illustrates file input/output and string substitution.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

#!/usr/bin/python

# -*- coding: UTF-8 -*-

"""

htmlescape - Escape the given html file

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Replace the HTML reserved characters by their corresponding HTML entities.

" is replaced with "

& is replaced with &

< is replaced with <

> is replaced with >

Usage: htmlescape.py infile outfile

"""

import sys # Using sys.argv and sys.exit()

# Check if infile and outfile are given in the command-line arguments

if len(sys.argv) != 3:

print('Usage: ./htmlescape.py infile outfile')

sys.exit(1) # Return a non-zero value to indicate abnormal termination

# The "with-as" closes the files automatically upon exit.

with open(sys.argv[1]) as infile, open(sys.argv[2], 'w') as outfile:

for line in infile: # Process each line (including newline)

line = line.rstrip() # strip trailing (right) white spaces

# Encode HTML &, <, >, ". The order of substitution is important!

line = line.replace('&', '&') # Need to do first as the rest uses it

line = line.replace('<', '<')

line = line.replace('>', '>')

line = line.replace('"', '"')

outfile.write('%s\n' % line) # write() does not output newline

How it works

import sys (Line 14): We import the sys module (@ https://docs.python.org/3/library/sys.html). We retrieve the command-line arguments from the list sys.argv, where sys.argv[0] is the script name; and use sys.exit() (Line 18) to terminate the program.

with open(sys.argv[1]) as infile, open(sys.argv[2], 'w') as outfile: (Line 21): We use the with-as statement, which closes the files automatically at exit, to open the infile for read (default) and outfile for write ('w').

for line in infile: (Line 22): We use a foreach-in loop to process each line of the infile, where line belongs to the built-in class "str" (meant for string support @ https://docs.python.org/3/library/stdtypes.html#str). We use str class' member function rstrip() to strip the trailing (right) white spaces; and replace() for substitution.

str.rstrip([chars])

# Return a copy of the string with trailing (right) characters removed.

# The optional argument chars is a string specifying the characters to be removed.

# Default is whitespaces '\t\n '.

str.replace(old, new[, count])

# Return a copy of the string with ALL occurrences of substring old replaced by new.

# If the optional argument count is given, only the first count occurrences are replaced.

Python 3.2 introduces a new html module, with a function escape() to escape HTML reserved characters.

>>> import html

>>> html.escape('<p>Test "Escape&"</p>')

'<p>Test "Escape&"</p>'

1.10 Example files_rename.py - Rename Files

This example renames all the files in the given directory using regular expression (regex). It illustrates directory/file processing (using module os) and regular expression (using module re).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# -*- coding: UTF-8 -*-

"""

files_rename - Rename files in the directory using regex

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Rename all the files in the given directory (default to the current directory)

matching the regular expression from_regex by to_regex.

Usage: files_rename.py from_regex to_regex [dir|.]

Eg. Rename '.txt' to '.bak' in the current directory:

$ ./files_rename.py '\.txt' '.bak'

Eg. Rename files ending with '.txt' to '.bak' in directory '/temp'

$ ./files_rename.py '\.txt$' '.bak' '/temp'

Eg. Rename 0 to 9 with _0 to _9 via back reference in the current directory:

$ ./files_rename.py '([0-9])' '_\1'

"""

import sys # Using sys.argv, sys.exit()

import os # Using os.chdir(), os.listdir(), os.path.isfile(), os.rename()

import re # Using re.sub()

if not(3 <= len(sys.argv) <= 4): # logical operators are 'and', 'or', 'not'

print('Usage: ./files_rename.py from_regex to_regex [dir|.]')

sys.exit(1) # Return a non-zero value to indicate abnormal termination

# Change directory if given

if len(sys.argv) == 4:

dir = sys.argv[3]

os.chdir(dir) # change current working directory

count = 0 # count of files renamed

for oldFilename in os.listdir(): # list current directory, non-recursive

if os.path.isfile(oldFilename): # file only (not directory)

newFilename = re.sub(sys.argv[1], sys.argv[2], oldFilename)

if oldFilename != newFilename:

count += 1 # Update count

os.rename(oldFilename, newFilename)

print(oldFilename, '->', newFilename) # Print results

print("Number of files renamed:", count)

How it works

import os (Line 21): We import the os module (for operating system utilities @ https://docs.python.org/3/library/os.html), and use these functions:

os.listdir(path='.')

# Return a list containing the names of the entries in the directory given by path.

# Default is current working directory.

os.path.isfile(path)

# Return True if path is an existing regular file.

os.rename(src, dst, *, src_dir_fd=None, dst_dir_fd=None)

# Rename the file or directory src to dst.

import re (Line 22): We import the re module (for regular expression @ https://docs.python.org/3/library/re.html), and use this function:

re.sub(pattern, replacement, string, count=0, flags=0)

# default count=0 replaces all matches.

2. Introduction

Python is created by Dutch Guido van Rossum around 1991. Python is an open-source project. The mother site is www.python.org.

The main features of Python are:

Python is an easy and intuitive language. Python scripts are easy to read and understand.

Python (like Perl) is expressive. A single line of Python code can do many lines of code in traditional general-purpose languages (such as C/C++/Java).

Python is free and open-source. It is cross-platform and runs on Windows, Linux/UNIX, and Mac OS X.

Python is well suited for rapid application development (RAD). You can code an application in Python in much shorter time than other general-purpose languages (such as C/C++/Java). Python can be used to write small applications and rapid prototypes, but it also scales well for developing large-scale project.

Python is a scripting language and dynamically typed. Like most of the scripting languages (e.g., Perl, JavaScript), Python associates types with objects, instead of variables. That is, a variable can be assigned a value of any type, a list (array) can contain objects of different types.

Python provides automatic memory management. You do not need to allocate and free memory in your programs.

Python provides high-level data types such as dynamic array and dictionary (or associative array).

Python is object-oriented.

Python is not a fully compiled language. It is compiled into internal byte-codes, which is then interpreted. Hence, Python is not as fast as fully-compiled languages such as C/C++.

Python comes with a huge set of libraries including graphical user interface (GUI) toolkit, web programming library, networking, and etc.

Python has 3 versions:

Python 1: the initial version.

Python 2: released in 2000, with many new features such as garbage collector and support for Unicode.

Python 3 (Python 3000 or py3k): A major upgrade released in 2008. Python 3 is NOT backward compatible with Python 2.

Python 2 or Python 3?

Currently, two versions of Python are supported in parallel, version 2.7 and version 3.5. There are unfortunately incompatible. This situation arises because when Guido Van Rossum (the creator of Python) decided to bring significant changes to Python 2, he found that the new changes would be incompatible with the existing codes. He decided to start a new version called Python 3, but continue maintaining Python 2 without introducing new features. Python 3.0 was released in 2008, while Python 2.7 in 2010.

AGAIN, TAKE NOTE THAT PYTHON 2 AND PYTHON 3 ARE NOT COMPATIBLE!!! You need to decide whether to use Python 2 or Python 3. Start your new projects using Python 3. Use Python 2 only for maintaining legacy projects.

To check the version of your Python, issue this command:

$ Python --version

3. Installation and Getting Started

3.1 Installation

For Newcomers to Python (Windows, Mac OSX, Ubuntu)

I suggest you install "Anaconda distribution" of Python 3, which includes a Command Prompt, IDEs (Jupyter Notebook and Spyder), and bundled with commonly-used packages (such as NumPy, Matplotlib and Pandas that are used for data analytics).

Goto Anaconda mother site (@ https://www.anaconda.com/) ⇒ Choose "Anaconda Distribution" Download ⇒ Choose "Python 3.x" ⇒ Follow the instructions to install.

Check If Python Already Installed and its Version

To check if Python is already installed and its the version, issue the following command:,

# Python 3

$ python3 --version

Python 3.5.2

# Python 2

$ python2 --version

Python 2.7.12

Ubuntu (16.04LTS)

Both the Python 3 and Python 2 should have already installed by default. Otherwise, you can install Python via:

# Installing Python 3

$ sudo apt-get install python3

# Installing Python 2

$ sudo apt-get install python2

To verify the Python installation:

# Locate the Python Interpreters

$ which python2

/usr/bin/python2

$ which python3

/usr/bin/python3

$ ll /usr/bin/python*

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 9 xxx xx xxxx python -> python2.7*

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 9 xxx xx xxxx python2 -> python2.7*

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 3345416 xxx xx xxxx python2.7*

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 9 xxx xx xxxx python3 -> python3.5*

-rwxr-xr-x 2 root root 3709944 xxx xx xxxx python3.5*

-rwxr-xr-x 2 root root 3709944 xxx xx xxxx python3.5m*

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 10 xxx xx xxxx python3m -> python3.5m*

# Clearly,

# "python" and "python2" are symlinks to "python2.7".

# "python3" is a symlink to "python3.5".

# "python3m" is a symlink to "python3.5m".

# "python3.5" and "python3.5m" are hard-linked (having the same inode and hard-link count of 2), i.e., identical.

Windows

You could install either:

"Anaconda Distribution" (See previous section)

Plain Python from Python Software Foundation @ https://www.python.org/download/, download the 32-bit or 64-bit MSI installer, and run the downloaded installer.

Under the Cygwin (Unix environment for Windows) and install Python (under the "devel" category).

Mac OS X

[TODO]

3.2 Documentation

Python documentation and language reference are provided online @ https://docs.python.org.

3.3 Getting Started with Python Interpreter

Start the Interactive Python Interpreter

You can run the "Python Interpreter" in interactive mode under a "Command-Line Shell" (such as Anaconda Prompt, Windows' CMD, Mac OS X's Terminal, Ubuntu's Bash Shell):

$ python # Also try "python3" and "python2" and check its version

Python 3.7.0

......

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

The Python's command prompt is denoted as >>>. You can enter Python statement at the Python's command prompt, e.g.,

>>> print('hello, world')

hello, world

# 2 raises to power of 88. Python's int is unlimited in size

>>> print(2 ** 88)

309485009821345068724781056

# Python supports floating-point number

>>> print(8.01234567890123456789)

8.012345678901234

# Python supports complex number

>>> print((1+2j) * (3+4j))

(-5+10j)

# Create a variable with an numeric value

>>> x = 123

# Show the value of the variable

>>> x

123

# Create a variable with a string

>>> msg = 'hi!'

# Show the value of the variable

>>> msg

'hi!'

# Exit the interpreter

>>> exit() # or Ctrl-D or Ctrl-Z-Enter

To exit Python Interpreter:

exit()

(Mac OS X and Ubuntu) Ctrl-D

(Windows) Ctrl-Z followed by Enter

3.4 Writing and Running Python Scripts

First Python Script - hello.py

Use a programming text editor to write the following Python script and save as "hello.py" in a directory of your choice:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# -*- coding: UTF-8 -*-

"""

hello: First Python Script

"""

myStr = 'Hello, world' # Strings are enclosed in single qoutes or double quotes

print(myStr)

myInt = 2 ** 88 # 2 to the power of 88. Python's integer is unlimited in size!

print(myInt)

myFloat = 8.01234567890123456789 # Python support floating-point numbers

print(myFloat)

myComplex = (1+2j) / (3-4j) # Python supports complex numbers!

print(myComplex)

myLst = [11, 22, 33] # Python supports list (dynamic array)

print(myLst[1])

How it Works

By convention, Python script (module) filenames are in all-lowercase (e.g., hello).

EOL Comment: Statements beginning with a # until the end-of-line (EOL) are comments.

#!/usr/bin/env python3 (Line 1) is applicable to the Unix environment only. It is known as the Hash-Bang (or She-Bang) for specifying the location of Python Interpreter, so that the script can be executed directly as a standalone program.

# -*- coding: UTF-8 -*- (Line 2, optional) specifies the source encoding scheme for saving the source file. We choose and recommend UTF-8 for internationalization. This special format is recognized by many popular editors for saving the source code in the specified encoding format.

""" hello ...... """ (Line 3-5): The script begins by the so-called doc-string to provide the documentation for this Python module. Doc-string is typically a multi-line string (delimited by triple-single or triple-double quoted), which can be extracted from the source file to create documentation.

Variables: We create variables myStr, myInt, myFloat, myComplex, myLst (Line 6, 8, 10, 12, 14) by assignment values into them.

Python's strings can be enclosed with single quotes '...' (Line 6) or double quotes "...".

Python's integer is unlimited in size (Line 8).

Python support floating-point numbers (Line 10).

Python supports complex numbers (Line 12) and other high-level data types.

Python supports a dynamic array called list (Line 14), represented by lst=[v1, v2, ..., vn]. The element can be retrieved via index lst[i] (Line 15).

print(aVar): The print() function can be used to print the value of a variable to the console.

Expected Output

The expected outputs are:

Hello, world

309485009821345068724781056

8.012345678901234

(-0.2+0.4j)

22

Running Python Scripts

You can develop/run a Python script in many ways - explained in the following sections.

Running Python Scripts in Command-Line Shell (Anaconda Prompt, CMD, Terminal, Bash)

You can run a python script via the Python Interpreter under the Command-Line Shell:

$ cd <dirname> # Change directory to where you stored the script

$ python hello.py # Run the script via the Python interpreter

# (Also try "python3 hello.py" and "python2 hello.py"

Unix's Executable Shell Script

In Linux/Mac OS X, you can turn a Python script into an executable program (called Shell Script or Executable Script) by:

Start with a line beginning with #! (called "hash-bang" or "she-bang"), followed by the full-path name to the Python Interpreter, e.g.,

#!/usr/bin/python3

......

To locate the Python Interpreter, use command "which python" or "which python3".

Make the file executable via chmod (change file mode) command:

$ cd /path/to/project-directory

$ chmod u+x hello.py # enable executable for user-owner

$ ls -l hello.py # list to check the executable flag

-rwxrw-r-- 1 uuuu gggg 314 Nov 4 13:21 hello.py

You can then run the Python script just like any executable programs. The system will look for the Python Interpreter from the she-bang line.

$ cd /path/to/project-directory

$ ./hello.py

The drawback is that you have to hard code the path to the Python Interpreter, which may prevent the program from being portable across different machines.

Alternatively, you can use the following to pick up the Python Interpreter from the environment:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

......

The env utility will locate the Python Interpreter (from the PATH entries). This approach is recommended as it does not hard code the Python's path.

Windows' Exeutable Program

In Windows, you can associate ".py" file extension with the Python Interpretable, to make the Python script executable.

Running Python Scripts inside Python's Interpreter

To run a script "hello.py" inside Python's Interpreter:

# Python 3 and Python 2

$ python3

......

>>> exec(open('/path/to/hello.py').read())

# Python 2

$ python2

......

>>> execfile('/path/to/hello.py')

# OR

>>> exec(open('/path/to/hello.py'))

You can use either absolute or relative path for the filename. But, '~' (for home directory) does not work?!

The open() built-in function opens the file, in default read-only mode; the read() function reads the entire file.

3.5 Interactive Development Environment (IDE)

Using an IDE with graphic debugging can greatly improve on your productivity.

For beginners, I recommend:

Python Interpreter (as described above)

Python IDLE

Jupyter Notebook (especially for Data Analytics)

For Webapp developers, I recommend:

Eclipse with PyDev

PyCharm

See "Python IDE and Debuggers" for details.

4. Python Basic Syntaxes

4.1 Comments

A Python comment begins with a hash sign (#) and last till the end of the current line. Comments are ignored by the Python Interpreter, but they are critical in providing explanation and documentation for others (and yourself three days later) to read your program. Use comments liberally.

There is NO multi-line comment in Python?! (C/C++/Java supports multi-line comments via /* ... */.)

4.2 Statements

A Python statement is delimited by a newline. A statement cannot cross line boundaries, except:

An expression in parentheses (), square bracket [], and curly braces {} can span multiple lines.

A backslash (\) at the end of the line denotes continuation to the next line. This is an old rule and is NOT recommended as it is error-prone.

Unlike C/C++/C#/Java, you don't place a semicolon (;) at the end of a Python statement. But you can place multiple statements on a single line, separated by semicolon (;). For examples,

# One Python statement in one line, terminated by a newline.

# There is no semicolon at the end of a statement.

>>> x = 1 # Assign 1 to variable x

>>> print(x) # Print the value of the variable x

1

>>> x + 1

2

>>> y = x / 2

>>> y

0.5

# You can place multiple statements in one line, separated by semicolon.

>>> print(x); print(x+1); print(x+2) # No ending semicolon

1

2

3

# An expression in brackets [] can span multiple lines

>>> x = [1,

22,

333] # Re-assign a list denoted as [v1, v2, ...] to variable x

>>> x

[1, 22, 333]

# An expression in braces {} can also span multiple lines

>>> x = {'name':'Peter',

'gender':'male',

'age':21

} # Re-assign a dictionary denoted as {k1:v1, k2:v2,...} to variable x

>>> x

{'name': 'Peter', 'gender': 'male', 'age': 21}

# An expression in parentheses () can also span multiple lines

# You can break a long expression into several lines by enclosing it with parentheses ()

>>> x =(1 +

2

+ 3

-

4)

>>> x

2

# You can break a long string into several lines with parentheses () too

>>> s = ('testing ' # No commas

'hello, '

'world!')

>>> s

'testing hello, world!'

4.3 Block, Indentation and Compound Statements

A block is a group of statements executing as a unit. Unlike C/C++/C#/Java, which use braces {} to group statements in a body block, Python uses indentation for body block. In other words, indentation is syntactically significant in Python - the body block must be properly indented. This is a good syntax to force you to indent the blocks correctly for ease of understanding!!!

A compound statement, such as conditional (if-else), loop (while, for) and function definition (def), begins with a header line terminated with a colon (:); followed by the indented body block, as follows:

header_1: # Headers are terminated by a colon

statement_1_1 # Body blocks are indented (recommended to use 4 spaces)

statement_1_2

......

header_2:

statement_2_1

statement_2_2

......

# You can place the body-block in the same line, separating the statement by semi-colon (;)

# This is NOT recommended.

header_1: statement_1_1

header_2: statement_2_1; statement_2_2; ......

For examples,

# if-else

x = 0

if x == 0:

print('x is zero')

else:

print('x is not zero')

# or, in the same line

if x == 0: print('x is zero')

else: print('x is not zero')

# while-loop sum from 1 to 100

sum = 0

number = 1

while number <= 100:

sum += number

number += 1

print(sum)

# or, in the same line

while number <= 100: sum += number; number += 1

# Define the function sum_1_to_n()

def sum_1_to_n(n):

"""Sum from 1 to the given n"""

sum = 0;

i = 0;

while (i <= n):

sum += i

i += 1

return sum

print(sum_1_to_n(100)) # Invoke function

Python does not specify how much indentation to use, but all statements of the SAME body block must start at the SAME distance from the right margin. You can use either space or tab for indentation but you cannot mix them in the SAME body block. It is recommended to use 4 spaces for each indentation level.

The trailing colon (:) and body indentation is probably the most strange feature in Python, if you come from C/C++/C#/Java. Python imposes strict indentation rules to force programmers to write readable codes!

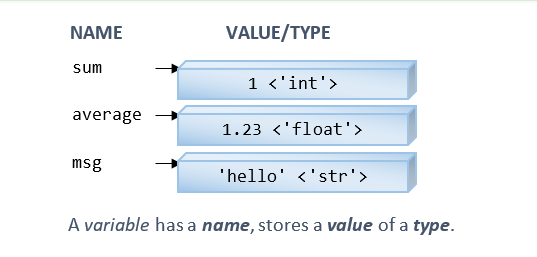

4.4 Variables, Identifiers and Constants

Like all programming languages, a variable is a named storage location. A variable has a name (or identifier) and holds a value.

Like most of the scripting interpreted languages (such as JavaScript/Perl), Python is dynamically typed. You do NOT need to declare a variable before using it. A variables is created via the initial assignment. (Unlike traditional general-purpose static typed languages like C/C++/Java/C#, where you need to declare the name and type of the variable before using the variable.)

For example,

>>> sum = 1 # Create a variable called sum by assigning an integer into it

>>> sum

1

>>> type(sum) # Check the data type

<class 'int'>

>>> average = 1.23 # Create a variable called average by assigning a floating-point number into it

>>> average

1.23

>>> average = 4.5e-6 # Re-assign a floating-point value in scientific notation

>>> average

4.5e-06

>>> type(average) # Check the data type

<class 'float'>

>>> average = 78 # Re-assign an integer value

>>> average

78

>>> type(average) # Check the data type

<class 'int'> # Change to 'int'

>>> msg = 'Hello' # Create a variable called msg by assigning a string into it

>>> msg

'Hello'

>>> type(msg) # Check the data type

<class 'str'>

As mentioned, Python is dynamic typed. Python associates types with the objects, not the variables, i.e., a variable can hold object of any types, as shown in the above examples.

Rules of Identifier (Names)

An identifier starts with a letter (A-Z, a-z) or an underscore (_), followed by zero or more letters, underscores and digits (0-9). Python does not allow special characters such as $ and @.

Keywords

Python 3 has 35 reserved words, or keywords, which cannot be used as identifiers.

True, False, None (boolean and special literals)

import, as, from

if, elif, else, for, in, while, break, continue, pass, with (flow control)

def, return, lambda, global, nonlocal (function)

class

and, or, not, is, del (operators)

try, except, finally, raise, assert (error handling)

await, async, yield

Variable Naming Convention

A variable name is a noun, or a noun phrase made up of several words. There are two convenctions:

In lowercase words and optionally joined with underscore if it improves readability, e.g., num_students, x_max, myvar, isvalid, etc.

In the so-called camel-case where the first word is in lowercase, and the remaining words are initial-capitalized, e.g., numStudents, xMax, yMin, xTopLeft, isValidInput, and thisIsAVeryLongVariableName. (This is the Java's naming convention.)

Recommendations

It is important to choose a name that is self-descriptive and closely reflects the meaning of the variable, e.g., numStudents, but not n or x, to store the number of students. It is alright to use abbreviations, e.g., idx for index.

Do not use meaningless names like a, b, c, i, j, k, n, i1, i2, i3, j99, exercise85 (what is the purpose of this exercise?), and example12 (What is this example about?).

Avoid single-letter names like i, j, k, a, b, c, which are easier to type but often meaningless. Exceptions are common names like x, y, z for coordinates, i for index. Long names are harder to type, but self-document your program. (I suggest you spend sometimes practicing your typing.)

Use singular and plural nouns prudently to differentiate between singular and plural variables. For example, you may use the variable row to refer to a single row number and the variable rows to refer to many rows (such as a list of rows - to be discussed later).

Constants

Python does not support constants, where its contents cannot be modified. (C supports constants via keyword const, Java via final.)

It is a convention to name a variable in uppercase (joined with underscore), e.g., MAX_ROWS, SCREEN_X_MAX, to indicate that it should not be modified in the program. Nevertheless, nothing prevents it from being modified.

4.5 Data Types: Number, String and List

Python supports various number type such as int (for integers such as 123, -456), float (for floating-point number such as 3.1416, 1.2e3, -4.5E-6), and bool (for boolean of either True and False).

Python supports text string (a sequence of characters). In Python, strings can be delimited with single-quotes or double-quotes, e.g., 'hello', "world", '' or "" (empty string).

Python supports a dynamic-array structure called list, denoted as lst = [v1, v2, ..., vn]. You can reference the i-th element as lst[i]. Python's list is similar to C/C++/Java's array, but it is NOT fixed size, and can be expanded dynamically during runtime.

I will describe these data types in details in the later section.

4.6 Console Input/Output: input() and print() Built-in Functions

You can use built-in function input() to read input from the console (as a string) and print() to print output to the console. For example,

>>> x = input('Enter a number: ')

Enter a number: 5

>>> x

'5' # A quoted string

>>> type(x) # Check data type

<class 'str'>

>>> print(x)

5

# Cast input from the 'str' input to 'int'

>>> x = int(input('Enter an integer: '))

Enter an integer: 5

>>> x

5 # int

>>> type(x) # Check data type

<class 'int'>

>>> print(x)

5

print()

The built-in function print() has the following signature:

print(*objects, sep=' ', end='\n', file=sys.stdout, flush=False)

# Print objects to the text stream file (default standard output sys.stdout),

# separated by sep (default space) and followed by end (default newline).

For examples,

>>> print('apple') # Single item

apple

>>> print('apple', 'orange') # More than one items separated by commas

apple orange

>>> print('apple', 'orange', 'banana')

apple orange banana

print()'s separator (sep) and ending (end)

You can use the optional keyword-argument sep='x' to set the separator string (default is space), and end='x' for ending string (default is newline). For examples,

# print() with default newline

>>> for item in [1, 2, 3, 4]:

print(item) # default is newline

1

2

3

4

# print() without newline

>>> for item in [1, 2, 3, 4]:

print(item, end='') # suppress end string

1234

# print() with some arbitrary ending string

>>> for item in [1, 2, 3, 4]:

print(item, end='--')

1--2--3--4--

# Test separator between items

>>> print('apple', 'orange', 'banana') # default is space

apple orange banana

>>> print('apple', 'orange', 'banana', sep=',')

apple,orange,banana

>>> print('apple', 'orange', 'banana', sep=':')

apple:orange:banana

>>> print('apple', 'orange', 'banana', sep='|')

apple|orange|banana

>>> print('apple', 'orange', 'banana', sep='\n') # newline

apple

orange

banana

print in Python 2 vs Python 3

Recall that Python 2 and Python 3 are NOT compatible. In Python 2, you can use "print item", without the parentheses (because print is a keyword in Python 2). In Python 3, parentheses are required as print() is a function. For example,

# Python 3

>>> print('hello')

hello

>>> print 'hello'

File "<stdin>", line 1

print 'hello'

^

SyntaxError: Missing parentheses in call to 'print'

>>> print('aaa', 'bbb')

aaa bbb

# Treated as multiple arguments, printed without parentheses

# Python 2

>>> print('Hello')

Hello

>>> print 'hello'

hello

>>> print('aaa', 'bbb')

('aaa', 'bbb')

# Treated as a tuple (of items). Print the tuple with parentheses

>>> print 'aaa', 'bbb'

aaa bbb

# Treated as multiple arguments

Important: Always use print() function with parentheses, for portability!

5. Data Types and Dynamic Typing

Python has a large number of built-in data types, such as Numbers (Integer, Float, Boolean, Complex Number), String, List, Tuple, Set, Dictionary and File. More high-level data types, such as Decimal and Fraction, are supported by external modules.

You can use the built-in function type(varName) to check the type of a variable or literal.

5.1 Number Types

Python supports these built-in number types:

Integers (type int): e.g., 123, -456. Unlike C/C++/Java, integers are of unlimited size in Python. For example,

>>> 123 + 456 - 789

-210

>>> 123456789012345678901234567890 + 1

123456789012345678901234567891

>>> 1234567890123456789012345678901234567890 + 1

1234567890123456789012345678901234567891

>>> 2 ** 888 # Raise 2 to the power of 888

......

>>> len(str(2 ** 888)) # Convert integer to string and get its length

268 # 2 to the power of 888 has 268 digits

>>> type(123) # Get the type

<class 'int'>

>>> help(int) # Show the help menu for type int

You can also express integers in hexadecimal with prefix 0x (or 0X); in octal with prefix 0o (or 0O); and in binary with prefix 0b (or 0B). For examples, 0x1abc, 0X1ABC, 0o1776, 0b11000011.

Floating-point numbers (type float): e.g., 1.0, -2.3, 3.4e5, -3.4E-5, with a decimal point and an optional exponent (denoted by e or E). floats are 64-bit double precision floating-point numbers. For example,

>>> 1.23 * -4e5

-492000.0

>>> type(1.2) # Get the type

<class 'float'>

>>> import math # Using the math module

>>> math.pi

3.141592653589793

>>> import random # Using the random module

>>> random.random() # Generate a random number in [0, 1)

0.890839384187198

Booleans (type bool): takes a value of either True or False. Take note of the spelling in initial-capitalized.

>>> 8 == 8 # Compare

True

>>> 8 == 9

False

>>> type(True) # Get type

<class 'bool'>

>>> type (8 == 8)

<class 'bool'>

In Python, integer 0, an empty value (such as empty string '', "", empty list [], empty tuple (), empty dictionary {}), and None are treated as False; anything else are treated as True.

>>> bool(0) # Cast int 0 to bool

False

>>> bool(1) # Cast int 1 to bool

True

>>> bool('') # Cast empty string to bool

False

>>> bool('hello') # Cast non-empty string to bool

True

>>> bool([]) # Cast empty list to bool

False

>>> bool([1, 2, 3]) # Cast non-empty list to bool

True

Booleans can also act as integers in arithmetic operations with 1 for True and 0 for False. For example,

>>> True + 3

4

>>> False + 1

1

Complex Numbers (type complex): e.g., 1+2j, -3-4j. Complex numbers have a real part and an imaginary part denoted with suffix of j (or J). For example,

>>> x = 1 + 2j # Assign variable x to a complex number

>>> x # Display x

(1+2j)

>>> x.real # Get the real part

1.0

>>> x.imag # Get the imaginary part

2.0

>>> type(x) # Get type

<class 'complex'>

>>> x * (3 + 4j) # Multiply two complex numbers

(-5+10j)

Other number types are provided by external modules, such as decimal module for decimal fixed-point numbers, fraction module for rational numbers.

# floats are imprecise

>>> 0.1 * 3

0.30000000000000004

# Decimal are precise

>>> import decimal # Using the decimal module

>>> x = decimal.Decimal('0.1') # Construct a Decimal object

>>> x * 3 # Multiply with overloaded * operator

Decimal('0.3')

>>> type(x) # Get type

<class 'decimal.Decimal'>

5.2 Dynamic Typing and Assignment Operator

Recall that Python is dynamic typed (instead of static typed).

Python associates types with objects, instead of variables. That is, a variable does not have a fixed type and can be assigned an object of any type. A variable simply provides a reference to an object.

You do not need to declare a variable before using a variable. A variable is created automatically when a value is first assigned, which links the assigned object to the variable.

You can use built-in function type(var_name) to get the object type referenced by a variable.

>>> x = 1 # Assign an int value to create variable x

>>> x # Display x

1

>>> type(x) # Get the type of x

<class 'int'>

>>> x = 1.0 # Re-assign a float to x

>>> x

1.0

>>> type(x) # Show the type

<class 'float'>

>>> x = 'hello' # Re-assign a string to x

>>> x

'hello'

>>> type(x) # Show the type

<class 'str'>

>>> x = '123' # Re-assign a string (of digits) to x

>>> x

'123'

>>> type(x) # Show the type

<class 'str'>

Type Casting: int(x), float(x), str(x)

You can perform type conversion (or type casting) via built-in functions int(x), float(x), str(x), bool(x), etc. For example,

>>> x = '123' # string

>>> type(x)

<class 'str'>

>>> x = int(x) # Parse str to int, and assign back to x

>>> x

123

>>> type(x)

<class 'int'>

>>> x = float(x) # Convert x from int to float, and assign back to x

>>> x

123.0

>>> type(x)

<class 'float'>

>>> x = str(x) # Convert x from float to str, and assign back to x

>>> x

'123.0'

>>> type(x)

<class 'str'>

>>> len(x) # Get the length of the string

5

>>> x = bool(x) # Convert x from str to boolean, and assign back to x

>>> x # Non-empty string is converted to True

True

>>> type(x)

<class 'bool'>

>>> x = str(x) # Convert x from bool to str

>>> x

'True'

In summary, a variable does not associate with a type. Instead, a type is associated with an object. A variable provides a reference to an object (of a certain type).

Check Instance's Type: isinstance(instance, type)

You can also use the built-in function isinstance(instance, type) to check if the instance belong to the type. For example,

>>> isinstance(123, int)

True

>>> isinstance('a', int)

False

>>> isinstance('a', str)

True

The Assignment Operator (=)

In Python, you do not need to declare variables before using the variables. The initial assignment creates a variable and links the assigned value to the variable. For example,

>>> x = 8 # Create a variable x by assigning a value

>>> x = 'Hello' # Re-assign a value (of a different type) to x

>>> y # Cannot access undefined (unassigned) variable

NameError: name 'y' is not defined

Pair-wise Assignment and Chain Assignment

For example,

>>> a = 1 # Ordinary assignment

>>> a

1

>>> b, c, d = 123, 4.5, 'Hello' # Pair-wise assignment of 3 variables and values

>>> b

123

>>> c

4.5

>>> d

'Hello'

>>> e = f = g = 123 # Chain assignment

>>> e

123

>>> f

123

>>> g

123

Assignment operator is right-associative, i.e., a = b = 123 is interpreted as (a = (b = 123)).

del Operator

You can use del operator to delete a variable. For example,

>>> x = 8 # Create variable x via assignment

>>> x

8

>>> del x # Delete variable x

>>> x

NameError: name 'x' is not defined

Built-in Functions

Python provides many built-in functions for numbers, including:

Mathematical functions: round(), pow(), abs(), etc.

type() to get the type.

Type conversion functions: int(), float(), str(), bool(), etc.

Base radix conversion functions: hex(), bin(), oct().

For examples,

# Test built-in function round()

>>> x = 1.23456

>>> type(x)

<type 'float'>

# Python 3

>>> round(x) # Round to the nearest integer

1

>>> type(round(x))

<class 'int'>

# Python 2

>>> round(x)

1.0

>>> type(round(x))

<type 'float'>

>>> round(x, 1) # Round to 1 decimal place

1.2

>>> round(x, 2) # Round to 2 decimal places

1.23

>>> round(x, 8) # No change - not for formatting

1.23456

# Test other built-in functions

>>> pow(2, 5)

32

>>> abs(-4.1)

4.1

# Test base radix conversion

>>> hex(1234)

'0x4d2'

>>> bin(254)

'0b11111110'

>>> oct(1234)

'0o2322'

>>> 0xABCD # Shown in decimal by default

43981

# List built-in functions

>>> dir(__built-ins__)

['type', 'round', 'abs', 'int', 'float', 'str', 'bool', 'hex', 'bin', 'oct',......]

# Show number of built-in functions

>>> len(dir(__built-ins__)) # Python 3

151

>>> len(dir(__built-ins__)) # Python 2

144

# Show documentation of __built-ins__ module

>>> help(__built-ins__)

......

5.4 String

In Python, strings can be delimited by a pair of single-quotes ('...') or double-quotes ("..."). Python also supports multi-line strings via triple-single-quotes ('''...''') or triple-double-quotes ("""...""").

To place a single-quote (') inside a single-quoted string, you need to use escape sequence \'. Similarly, to place a double-quote (") inside a double-quoted string, use \". There is no need for escape sequence to place a single-quote inside a double-quoted string; or a double-quote inside a single-quoted string.

A triple-single-quoted or triple-double-quoted string can span multiple lines. There is no need for escape sequence to place a single/double quote inside a triple-quoted string. Triple-quoted strings are useful for multi-line documentation, HTML and other codes.

Python 3 uses Unicode character set to support internationalization (i18n).

>>> s1 = 'apple'

>>> s1

'apple'

>>> s2 = "orange"

>>> s2

'orange'

>>> s3 = "'orange'" # Escape sequence not required

>>> s3

"'orange'"

>>> s3 ="\"orange\"" # Escape sequence needed

>>> s3

'"orange"'

# A triple-single/double-quoted string can span multiple lines

>>> s4 = """testing

12345"""

>>> s4

'testing\n12345'

Escape Sequences for Characters (\code)

Like C/C++/Java, you need to use escape sequences (a back-slash + a code) for:

Special non-printable characters, such as tab (\t), newline (\n), carriage return (\r)

Resolve ambiguity, such as \" (for " inside double-quoted string), \' (for ' inside single-quoted string), \\ (for \).

\xhh for character in hex value and \ooo for octal value

\uxxxx for 4-hex-digit (16-bit) Unicode character and \Uxxxxxxxx for 8-hex-digit (32-bit) Unicode character.

Raw Strings (r'...' or r"...")

You can prefix a string by r to disable the interpretation of escape sequences (i.e., \code), i.e., r'\n' is '\'+'n' (two characters) instead of newline (one character). Raw strings are used extensively in regex (to be discussed in module re section).

Strings are Immutable

Strings are immutable, i.e., their contents cannot be modified. String functions such as upper(), replace() returns a new string object instead of modifying the string under operation.

For examples,

>>> s = "Hello, world" # Assign a string literal to the variable s

>>> type(s) # Get data type of s

<class 'str'>

>>> len(s) # Length

12

>>> 'ello' in s # The in operator

True

# Indexing

>>> s[0] # Get character at index 0; index begins at 0

'H'

>>> s[1]

'e'

>>> s[-1] # Get Last character, same as s[len(s) - 1]

'd'

>>> s[-2] # 2nd last character

'l'

# Slicing

>>> s[1:3] # Substring from index 1 (included) to 3 (excluded)

'el'

>>> s[1:-1]

'ello, worl'

>>> s[:4] # Same as s[0:4], from the beginning

'Hell'

>>> s[4:] # Same as s[4:-1], till the end

'o, world'

>>> s[:] # Entire string; same as s[0:len(s)]

'Hello, world'

# Concatenation (+) and Repetition (*)

>>> s = s + " again" # Concatenate two strings

>>> s

'Hello, world again'

>>> s * 3 # Repeat 3 times

'Hello, world againHello, world againHello, world again'

# str can only concatenate with str, not with int and other types

>>> s = 'hello'

>>> print('The length of \"' + s + '\" is ' + len(s)) # len() is int

TypeError: can only concatenate str (not "int") to str

>>> print('The length of \"' + s + '\" is ' + str(len(s)))

The length of "hello" is 5

# String is immutable

>>> s[0] = 'a'

TypeError: 'str' object does not support item assignment

Character Type?